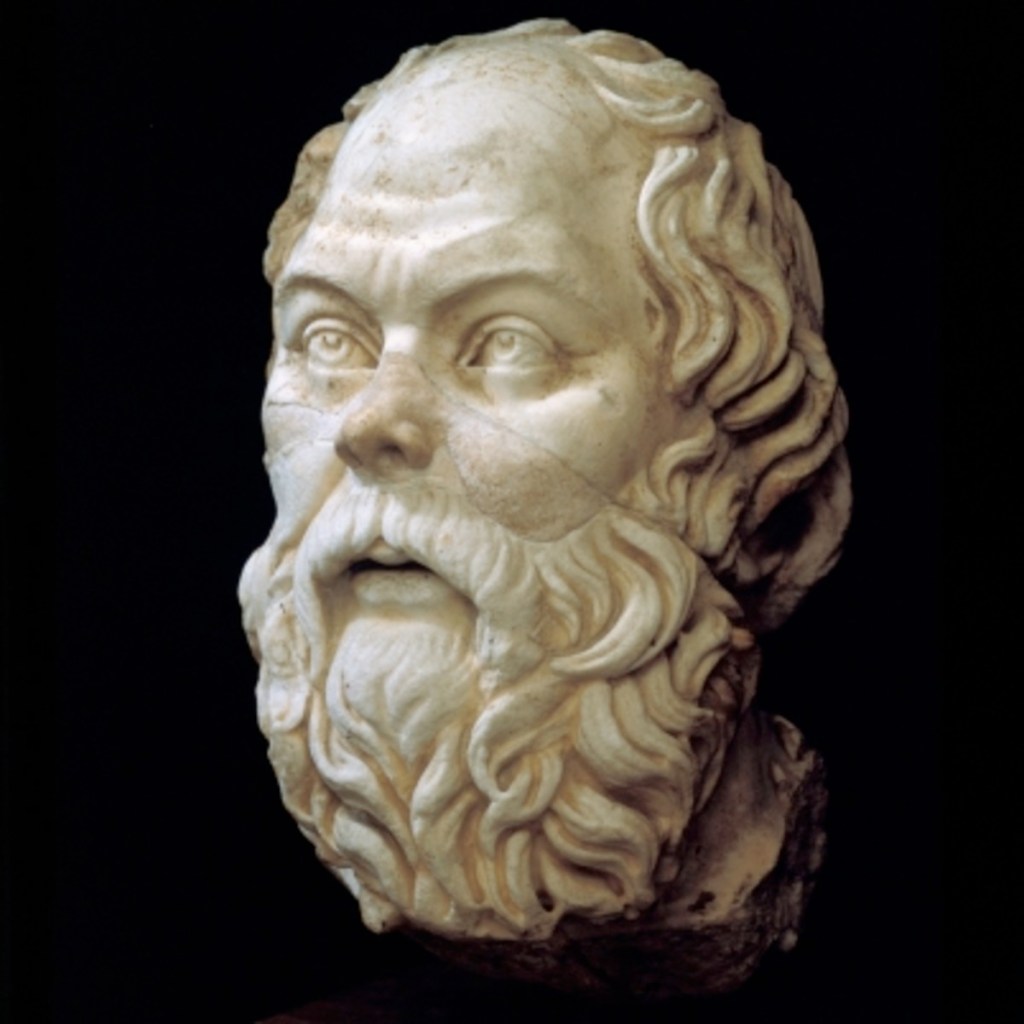

Socrates presents a figure difficult to surpass, that of an eternal hero of philosophical thought. But during his life, he nevertheless found his master, – or rather his mistress, by his own admission.

In the Symposium, Socrates reports that a « foreign », Dorian woman, Diotima, had made no secret of her doubts about Socrates’ limited abilities in truly higher matters.

Diotima had told him, without excessive oratory precaution, that he knew nothing about the ‘greatest mysteries’, and that he might not even be able to understand them…

Diotima had begun by inviting Socrates to « meditate on the strange state in which the love of fame puts one, as well as the desire to secure for the eternity of time an immortal glory.» i

Speaking of the « fruitful men according to the soul », such as poets or inventors, like Homer and Hesiod, who possess « the immortality of glory », or Lycurgus, « safeguard of Greece », she had emphasized their thirst for glory, and their desire for immortality. « It is so that their merit does not die, it is for such glorious fame, that all men do all that they do, and all the better they are. It is because immortality is the object of their love! » ii

Certainly, the love of immortality is something that Socrates is still able to understand. But there are much higher mysteries, and beyond that, the last, most sublime ‘revelation’…

« Now, the mysteries of love, Socrates, are those to which, no doubt, you could be initiated yourself. As for the last mysteries and the revelation, which, provided you follow the degrees of them correctly, are the goal of these last steps, I don’t know if you are capable of receiving them. I will nevertheless explain them to you, she said. As for me, I will spare nothing of my zeal; try, you, to follow me, if you are capable of it!» iii.

Diotima’s irony is obvious. No less ironic is the irony of Socrates about himself, since it is him who reports these demeaning words of Diotima.

Diotima keeps her word, and begins an explanation. For anyone who strives to reach ‘revelation’, one must begin by going beyond « the immense ocean of beauty » and even « the boundless love for wisdom ».

It is a question of going much higher still, to finally « perceive a certain unique knowledge, whose nature is to be the knowledge of this beauty of which I am now going to speak to you »iv.

And once again the irony becomes scathing.

« Try, she said, to give me your attention as much as you can. » v

So what is so hard to see, and what is this knowledge apparently beyond the reach of Socrates himself?

It is a question of discovering « the sudden vision of a beauty whose nature is marvelous », a « beauty whose existence is eternal, alien to generation as well as to corruption, to increase as well as to decrease; which, secondly, is not beautiful from this point of view and ugly to that other, not more so at this moment and not at that other, nor more beautiful in comparison with this, ugly in comparison with that (…) but rather she will show herself to him in herself and by herself, eternally united to herself in the uniqueness of her formal nature »vi.

With this « supernatural beauty » as a goal, one must « ascend continuously, as if by means of steps (…) to this sublime science, which is the science of nothing but this supernatural beauty alone, so that, in the end, we may know, in isolation, the very essence of Beauty. » vii

Diotima sums up this long quest as follows:

« It is at this point of existence, my dear Socrates, said the stranger from Mantinea, that, more than anywhere else, life for a man is worth living, when he contemplates Beauty in herself! May you one day see her! » viii

The ultimate goal then is: « succeeding in seeing Beauty in herself, in her integrity, in her purity, without mixture (…) and to see, in herself, the divine Beauty in the uniqueness of her formal nature »ix.

Moreover, it is not only a question of contemplating Beauty. It is still necessary to unite with her, in order to « give birth » and to become immortal oneself…

Diotima finally unveils her deepest idea:

« Do you really think that it would be a miserable life, that of the man whose gaze is turned towards this sublime goal; who, by means of what is necessaryx, contemplates this sublime object and unites with it? Don’t you think, she added, that by seeing Beauty by means of what she is visible by, it is only there that he will succeed in giving birth, not to simulacra of virtue, for it is not with a simulacrum that he is in contact, but with an authentic virtue, since this contact exists with the authentic real?

Now, to whom has given birth, to whom has nourished an authentic virtue, does it not belong to become dear to the Divinity? And does it not belong to him, more than to anyone else in the world, to make himself immortal? xi

To see Beauty herself, in herself, is the only sure way to make oneself immortal.

Is this what Socrates himself is « incapable of »?

Is then Socrates « incapable » of giving birth to virtue?

By his own admittance ?

________________

iPlato. Symposium. 208 c

iiPlato. Symposium208 d,e

iiiPlato. Symposium 209 e, 210 a

ivPlato. Symposium 210 d

vPlato. Symposium210 e

viPlato. Symposium 211 a,b

viiPlato. Symposium 211 c

viiiPlato. Symposium 211 d

ixPlato. Symposium 211 e

xIn order to do this, one must « use thought alone without resorting to sight or any other sensation, without dragging any of them along with reasoning » and « separate oneself from the totality of one’s body, since the body is what disturbs the soul and prevents it from acquiring truth and thought, and from touching reality. « Phédon 65 e-66a

« Within his soul each one possesses the power of knowledge (…) and is capable, directed towards reality, of supporting the contemplation of what is in the most luminous reality. And this is what we declare to be the Good » The Republic VII 518 c. » The talent of thinking is probably part of something that is much more divine than anything else. « Ibid. 518 e

xiPlato. Symposium. 212 a

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.