There were no ‘prophets’ in archaic and classical Greece, at least if we take this term in the sense of the nebîîm of Israel. On the other hand, there was a profusion of soothsayers, magicians, bacchae, pythias, sibyls and, more generally, a multitude of enthusiasts and initiates into the Mysteriesi … Auguste Bouché-Leclercq, author of a Histoire de la divination dans l’antiquité, emphasises the underlying unity of the sensibilities expressed through these various names: « The mystical effervescence which, with elements borrowed from the cult of the Nymphs, the religion of Dionysus and that of Apollo, had created prophetic enthusiasm, spread in all directions: it gave rise, wherever the cults generating divinatory intuition met, to the desire to inscribe in local traditions, as far back in time as possible and sheltered from any control, memories similar to those adorned by the oracle of Pytho. We can therefore consider these three instruments of the revealed word – pythias, chresmologists and sibyls – as having been created at the same time and as stemming from the same religious movement ».ii

However, it is important to appreciate the significant differences between these « three instruments of the revealed word ». For example, unlike the Pythia of Delphi, the sibyls were not linked to a particular sanctuary or a specific population. They were wanderers, individualists, free women. The character that best defined the sibyl, in comparison with the regular, appointed priestesses, was her « sombre, melancholy temperament, for she was dispossessed of her human and feminine nature, while possessed by the God ».iii The state of divine possession seemed to be a constant part of her nature, whereas the Pythia was visited only occasionally by inspiration.

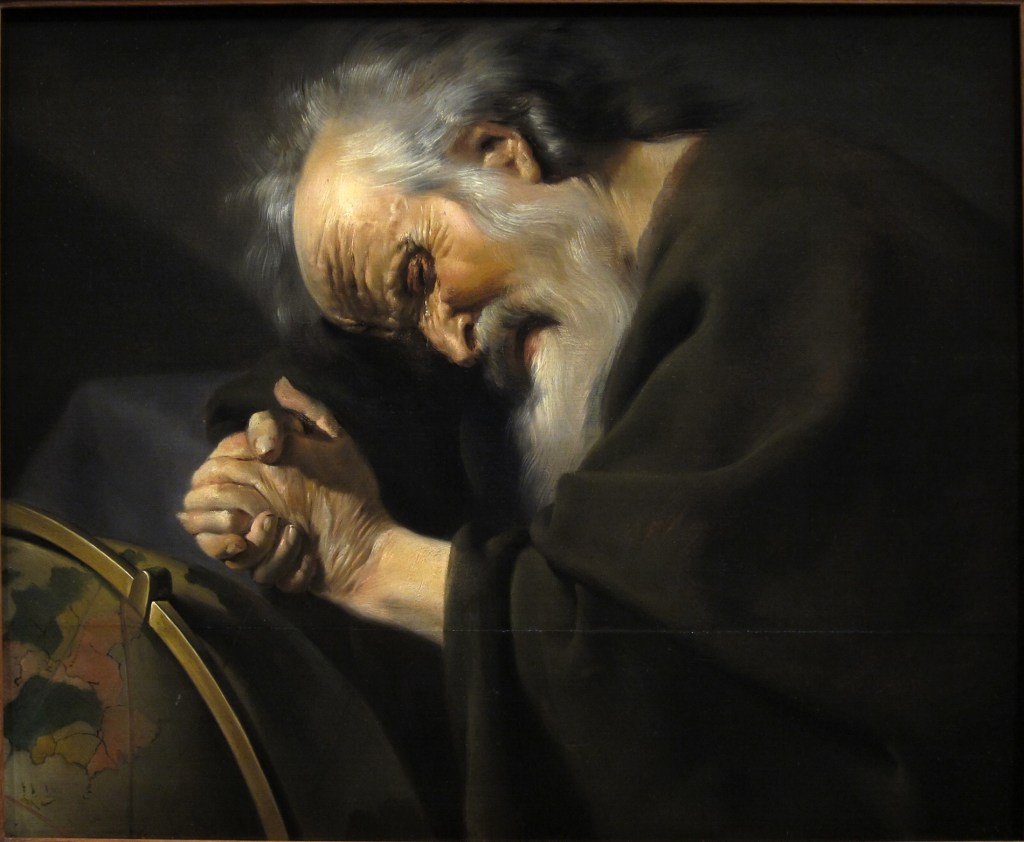

Heraclitus was the first classical author to mention the Sibyl and the Bacchanalia. He left behind a few fragments that were clearly hostile to Dionysian orgies. He condemns the exaltation and exultation of excess because, as a philosopher of the balance of opposites, he knows that they multiply the deleterious effects and ultimately lead to destruction and death. However, two of his fragments exude a curious ambiguity, a kind of hidden, latent sympathy for the figure of the Sibyl. « The Sibyl, neither smiling, nor adorned, nor perfumed, with her delirious mouth, making herself heard, crossed a thousand years with her voice, thanks to the God ».iv The Sibyl does not smile because she is constantly in the grip of the God. This « possession » is an unbearable burden for her. Her innermost consciousness is crushed by the divine presence. A totally passive instrument of the God who controls and dominates her, she has neither the desire nor even the strength to wear make-up or perfume. In contrast, the priestesses of the temples and official sanctuaries, fully aware of their role and social rank, were obliged to make an effort to represent themselves and put on a show.

The Sibyl belongs entirely to God, even if she denies it. She is surrendered to him, in a trance, body and soul. She has broken all ties with the world, except that of publicly delivering the divine word. It is because she has surrendered herself entirely to the divine spirit that it can command her voice, her language, and make her utter the unheard of, say the unforeseeable, explore the depths of the distant future. In the time of an oracle, the Sibyl can cross a thousand years in spirit, by the grace of God. All the divine power, present or future, is revealed in her. We know, or we sense, that her words will prove far wiser in their ‘madness’ than all human wisdom, though perhaps only in the distant future.

The Pythia of Delphi was devoted to Apollo. But the Sibyl, in her fierce independence, had no exclusive divine allegiance. She might be in contact with other gods, Dionysus, Hades or Zeus himself. According to Pausaniasv , the Sibyl, Herophilia, prophesied to the Delphians to reveal to them the « mind of Zeus », without worrying about Apollo, the tutelary god of Delphi, towards whom she harboured an old grudge.

In fact, we already knew that these different names for the God covered the same mystery. Dionysus, Hades or Zeus are « the same », because everything divine is « the same ». « If it wasn’t for Dionysus that they were doing the procession and sing the hymn to the shameful parts, they would do the most shameless things. But he is the same as Hades and Dionysus, the one for whom they rave and lead the bacchanal. »vi

Heraclitus knows and affirms that Hades and Dionysus are « the same » God, because in their profound convergence, and despite their apparent opposition (Hades, god of death / Dionysus, god of life), their intrinsic unity and common essence emerge, and their true transcendence reveals itself. Those who live only in Dionysian enthusiasm, in bloody bacchanals, are inevitably doomed to death. On the other hand, those who know how to dominate and ride ecstasy can go far beyond the loss of self-consciousness. They can surpass even the initiated consciousness of the mystics, reach a transcendent level of revelation, and finally surpass the Mystery as such.

The Dionysian bacchanals, enthusiastic and ecstatic, ended wit the death of the victims, who were torn apart, butchered and devoured. Heraclitus recognises In ‘Dionysus/Hades’, a dual essence, two ‘opposites’ that are also ‘the same’, enabling us to transcend death through a genuine ecstasy that is not corporeal or sensual, but intuitive and spiritual. Heraclitus rejects the excesses of Dionysian ecstasy and the death that puts an end to them. He is fascinated by the Sibyl, for she alone, and singularly alone, stands alive and ecstatic at the crossroads of life and death. While she is awake, the Sibyl sees death still at work: « Death is all we see, awake… ».vii Made a Sibyl by the God, and possessed by him against her will, she is, in a way, dead to herself and her femininity. She allows herself to be passively « taken » by God, she abandons herself, to allow the life of God to live in her. Living in God by dying to herself, she also dies of this divine life, by giving life to his words. Heraclitus seems to have drawn inspiration from the Sibyl in this fragment: « Immortals, mortals, mortals, immortals; living from those death, dying from those life ».viii Given its unique position as an intermediary between the living and the dead, between the divine and the human, it has been said that the Sibylline type was « one of the most original and noble creations of religious sentiment in Greece ».ix In ancient Greece, the Sibyl certainly represented a new state of consciousness, which it is important to highlight.

Isidore of Seville reports that, according to the best-informed authors, there were historically ten sibyls. The first appeared in Persia, or Chaldeax , the second in Libya, the third in Delphi, the fourth was Cimmerian from Italy. The fifth, « the noblest and most honoured of them all », was Eritrean and called Herophilia, and is thought to be of Babylonian origin. The sixth lived on the island of Samos, the seventh in the city of Cumae in Campania. The eighth came from the plains of Troy and radiated out over the Hellespont, the ninth was Phrygian and the tenth Tiburtine [i.e. operating in Tivoli, the ancient name of Tibur, in the province of Rome].xi Isidore also points out that, in the Aeolian dialect, God was said to be Σιός (Sios) and the word βουλή meant ‘spirit’. From this he deduced that sibyl, in Greek Σιϐυλλα, would be the Greek name for a function, not a proper name, and would be equivalent to Διὸς βουλή or θεοϐουλή (‘the spirit of God’). This etymology was also adopted by several Ancients (Varron, Lactantius,…). But this was not the opinion of everyone. Pausanias, noting that the prophetess Herophilia, cited by Plutarchxii and, as we have just seen, by Isidore, was called ‘Sibyl’ by the Libyansxiii , suggests that Σιϐυλλα, Sibyl, would be the metathesis or anagram of Λίϐυσσα, Libyssa, ‘the Libyan’, which would be an indication of the Libyan origin of the word sibyl. This name was later altered to Elyssa, which became the proper name of the Libyan sibylxiv . There have been many other etymologies in the past, more or less far-fetched or contrived, which preferred to turn to Semitic, Hebrew or Arabic roots, without winning conviction. In short, the problem of the etymology of sibyl is « for the moment a hopeless problem »xv . The history of the sibyl’s name, and the variety of places where it has been used around the Mediterranean and in the Middle East, bear witness to its influence on people’s minds, and to the strength of its personality.

But who was she really?

The Sibyl was first and foremost a woman’s voice in a trance, a voice that seemed to emanate from an abstract, invisible being of divine origin. Witnesses on the lookout wrote down everything that came out of this ‘delirious mouth’. Collections of Sibylline oracles were produced, free from any priestly intervention or established political or religious interests, at least at the origin of the Sibylline phenomenon. Much later, because of its centuries-long success, it was used to serve specific or apologetic interests.xvi In essence, the Sibyl manifested a pure prophetic spirit, contrasting with the conventional, regulated techniques of divination emanating from priestly guilds duly supervised by the powers of the day. It highlighted the structural antagonism between free inspiration, expressing the words of God himself without mediation or pretense, and the deductive divinatory practices of clerical oracles, taking advantage of the privileges of the priests attached to the Temples. Sibylline manticism could also be interpreted as a reaction against the monopoly of the Apollonian clergy, the lucrative privileges of professional diviners and competition from other ‘chresmologists’, whether Dionysian or Orphic.

The latent hostility between the Sibyl and Apollo can be explained by the constant efforts of the Sibyl to take away from the Apollonian priests the monopoly of intuitive and ceremonial divination and replace it with the testimony of direct revelation.

But there is another, more fundamental, and more psychological reading. The Sibyl is a nymph enslaved, submissive to the God. Her intelligence is literally « possessed » by Apollo, she is « furious » about it, but her heart is not takenxvii . In her trance, the Sibyl is dominated by what I would call her « unhappy consciousness ». We know that Hegel defines unhappy consciousness as consciousness that is at once « unique, undivided » and « double »xviii .

The Sibyl is ‘unhappy’ because she is aware that a consciousness other than her own is present within her, in this case that of God. What’s worse, it’s a God she doesn’t love, and who has taken complete possession of her consciousness. And her consciousness is as aware as she is of these two consciousnesses at once.

If you feel that referring to Hegel is too anachronistic, you can turn to authors from the 3rd century BC: Arctinos of Miletus, Lesches of Lesbos, Stasinos, or Hegesinos of Cyprusxix who portrayed Cassandra as the type of unhappy, sad, abandoned sibyl who was thought to be mad. Cassandra became the archetypal model of the sibyl, both messenger and victim of Apollo. According to the myth, Cassandra (or ‘Alexandra’, a name which means « she who drives men away or repels them »xx ) was given the gift of divination and foreknowledge by the grace of Apollo, who fell in love with her and wished to possess her. However, having accepted this gift, Cassandra was unwilling to give him her virginity in return, and « repulsed » him. Dejected by this refusal, he spat in her mouth, condemning her to an inability to express herself intelligibly and never to be believed. Lycophron, in his poem Alexandra, describes Cassandra as « the Sibyl’s interpreter », speaking in « confused, muddled, unintelligible words »xxi . The expression « the Sibyl’s interpreter » found in several translations is itself an interpretation… In Lycophron’s original text, we read: ἢ Μελαγκραίρας κόπις, literally « the sacrificial knife (κόπις) of Melankraira (Μελαγκραίρα) ». The sacrificial knife, as an instrument of divination, can be interpreted metonymically as ‘interpretation’ of the divine message, or as ‘the interpreter’ herself. Melankraira is one of the Sibyl’s nicknames. It literally means « black head ». This nickname is no doubt explained by the obscurity of her oracles or the unintelligibility of her words. A. Bouché-Leclercq hypothesises that Lycophron, in using this nickname, had been reminded of Aristotle’s doctrine associating the prophetic faculty with « melancholy », i.e. the « black bile », the melancholikè krasis xxii, whose role in visionaries, prophets and other « enthusiasts » has already been mentioned.

We could perhaps also see here, more than two millennia ahead of time, a sort of anticipation of the idea of the unconscious, as the « black head » could be associated by metonymy with the idea of « black » thought, i.e. « obscure » thought, and thus with the psychology of the depths.

In any case, Cassandra’s confusion of expression and her inability to make herself understood were a consequence of Apollo’s vengeance, as was her condemnation to being able to predict the future only in terms of misfortune, death and ruin.xxiii

Cassandra, the « knife » of the Melankraira, sung by Lycophron (320 BC – 280 BC) had then become the poetic reincarnation of a much older archetype. When the religious current of Orphism, which emerged in the 6th century BC, began to gain momentum in the 5th century BC, authors opposed to the Orphics were already saying that the Sibyl was « older than Orpheus » to refute the latter’s claims. It was even possible to trace the Sibyl back to before the birth of Zeus himself, and therefore before all the Olympian gods… The Sibyl was identified with Amalthea, a nymph who, according to Cretan and Pelasgian traditions, had been Zeus’ nurse. The choice of Amalthea was very fortunate, because it gave the Sibyl an age that exceeded that of the Olympian gods themselves. Secondly, it did not prevent us from recognising the Ionian origin of the Sibyl, Amalthea being linked indirectly, through the Cretan Ida, to the Trojan « Ida », where Rhea, the mother of Zeus, also dwelled. In other words, Amalthea was linked to the Phrygian Kybele or the Hellenised Great Mother.xxiv I think it is essential to emphasise that this ascent to the origins of the gods reveals that gods as lofty as Apollo and even Zeus also had a ‘mother’ and a ‘nurse’. Their mothers or nurses were, therefore, before them, because they gave them lifexxv .

The awareness of a pre-existing anteriority to the divine (in its mythical aspect) can also be interpreted as a radical advance in consciousness : i.e. as the symptom of a surpassing of mythological thought by itself, – as a surpassing by human consciousness of any prior representation on what constitutes the essence of the Gods.

This surpassing highlights an essential characteristic of consciousness, that of being an obscure power, or a power emanating from the Obscure, as the Sibyl’s name Melankraira explicitly indicates. Sibyl’s consciousness discovers that she must confront at once both the pervasive, dominant presence of the God, and her own, obscure, abyssmal depth. She discovers that she can free herself from the former, and that she can also surpass herself, and all her own profound darkness.

____________

iHeraclitus, Fragment 14: « Wanderers in the night: magi, bacchants, bacchantes, initiates. In things considered by men as Mysteries, they are initiated into impiety. »

iiA. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire de la divination dans l’antiquité, Tome II, Ed. Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1880, p.142

iiiMarcel Conche, in Heraclitus, Fragments, PUF, 1987, p. 154, note 1

ivHeraclitus. Fragment 92

vPausanias, X,12,6

viHeraclitus. Fragment 15

viiHeraclitus. Fragment 21

viiiHeraclitus. Fragment 62

ixA. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire de la divination dans l’antiquité, Tome II, Ed. Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1880, p.133

xIt should be noted that three centuries after Isidore of Seville (~565-636), the Encyclopaedia Souda (10th century), while repeating the rest of the information provided by Isidore, nevertheless states that the first Sibyl was among the Hebrews and that she bore the name Sambethe, according to certain sources: « She is called Hebrew by some, also Persian, and she is called by the proper name Sambethe from the race of the most blessed Noah; she prophesied about those things said with regard to Alexander [sc. the Great] of Macedon; Nikanor, who wrote a Life of Alexander, mentions her;[1] she also prophesied countless things about the lord Christ and his advent. But the other [Sibyls] agree with her, except that there are 24 books of hers, covering every race and region. As for the fact that her verses are unfinished and unmetrical, the fault is not that of the prophetess but of the shorthand-writers, unable to keep up with the rush of her speech or else uneducated and illiterate; for her remembrance of what she had said faded along with the inspiration. And on account of this the verses appear incomplete and the train of thought clumsy — even if this happened by divine management, so that her oracles would not be understood by the unworthy masses.

[Note] that there were Sibyls in different places and times and they numbered ten.[2] First then was the Chaldaean Sibyl, also [known as] Persian, who was called Sambethe by name. Second was the Libyan. Third was the Delphian, the one born in Delphi. Fourth was the Italian, born in Italian Kimmeria. Fifth was the Erythraian, who prophesied about the Trojan war. Sixth was the Samian, whose proper name was Phyto; Eratosthenes wrote about her.[3] Seventh was the Cumaean, also [called] Amalthia and also Hierophile. Eighth was the Hellespontian, born in the village of Marmissos near the town of Gergition — which were once in the territory of the Troad — in the time of Solon and Cyrus. Ninth was the Phrygian. Tenth was the Tiburtine, Abounaia by name. They say that the Cumaean brought nine books of her own oracles to Tarquinus Priscus, then the king of the Romans; and when he did not approve, she burned two books. [Note] that Sibylla is a Roman word, interpreted as « prophetess », or rather « seer »; hence female seers were called by this one name. Sibyls, therefore, as many have written, were born in different times and places and numbered ten. »

xiIsidore of Seville. The Etymologies. VIII,viii. Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 181

xiiPlutarch. « Why the Pythia no longer renders her oracles in verse ». Moral works. Translation from the Greek by Ricard. Tome II , Paris, 1844, p.268

xiiiPausanias, X, 12, 1

xivIt is also another name of Queen Dido.

xvA. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire de la divination dans l’antiquité, Tome II, Publisher Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1880, p.139, Note 1.

xviThe article « sibyl » in the Thesaurus of the Encyclopaedia Universalis (Paris, 1985) states, for example, on page 2048: « The Jewish sibyl corresponds to the literature of the Sibylline Oracles. The Hellenistic Jews, like the Christians, reworked the existing Sibylline Books, and then composed their own. As early as the 2nd century, the Jews of Alexandria used the sibylline genre as a means of propaganda. Twelve books of these collections of oracles are in our possession (…) The third book of the Sibylline Oracles is the most important of the collection, from which it is the source and model; it is also the most typically Jewish. A pure Homeric pastiche, it reflects Greek traditions, beliefs and ideas (Hesiod’s myth of the races) and Eastern ones (the ancient Babylonian doctrine of the cosmic year). Despite this cultural gap, it remains a Jewish work of apocalypse. It is similar to the Ethiopian Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees. Israel’s monotheistic credo runs throughout.

xviiPausanias, X,12,2-3 : « [ the sibyl] Herophilus flourished before the siege of Troy, for she announced in her oracles that Helen would be born and brought up in Sparta to the misfortune of Asia and Europe, and that Troy would be taken by the Greeks because of her. The Delians recall a hymn by this woman about Apollo; in her verses she calls herself not only Herophilus but also Diana; in one place she claims to be Apollo’s lawful wife, in another her sister and then her daughter; she says all this as if she were furious and possessed by the god. In another part of her oracles, she claims that she was born of an immortal mother, one of the nymphs of Mount Ida, and of a mortal father. Here are her expressions: I was born of a race half mortal, half divine; my mother is immortal, my father lived on coarse food. Through my mother I come from Mount Ida; my homeland is the red Marpesse, consecrated to the mother of the gods and watered by the river Aïdonéus« .

xviiiThe unhappy consciousness remains « as an undivided, unique consciousness, and it is at the same time a doubled consciousness; itself is the act of one self-consciousness looking into another, and itself is both; and the unity of the two is also its own essence; but for itself it is not yet this very essence, it is not yet the unity of the two self-consciousnesses… ». G.W.F. Hegel. The Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by Jean Hyppolite. Aubier. 1941, p.177

xixQuoted in A. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire de la divination dans l’antiquité, Tome II, Éditeur Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1880, p.148.

xxThe name Alexandra (Alex-andra) can be interpreted as meaning « she who repels or pushes aside men » from the verb άλεξω, to push aside, to repel, and from ἀνήρ, man (as opposed to woman). Cf. Pa ul Wathelet, Les Troyens de l’Iliade. Mythe et Histoire, Paris, les Belles lettres, 1989.

xxi« From the interior of her prison there still escaped a last Siren song which, from her groaning heart, like a maenad of Claros, like the interpreter of the Sibyl, daughter of Neso, like another Sphinx, she exhaled in confused, muddled, unintelligible words. And I have come, O my king, to repeat to you the words of the young prophetess ». Lycophron. Alexandra. Translation by F.D. Dehèque. Ed. A. Durand and F. Klincksieck. Paris, 1853

xxiiRobert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, Oxford, 1621 (Original title: The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptoms, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up)

xxiii« In Cassandra, the prototype of the sibyls, mantic inspiration, while deriving from Apollo, bears the mark of a fierce and unequal struggle between the god and his interpreter. What’s more, not only was Cassandra pursued by Apollo’s vengeance, but she could only foretell misfortune. All she could see in the future was the ruin of her homeland, the bloody demise of her people and, at the end of her horizon, the tragic conclusion of her own destiny. Hence the sombre character and harshness of the Sibylline prophecies, which hardly foretold anything but calamities, and which undoubtedly owed to this pessimistic spirit the faith with which Heraclitus honoured them ». A. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire de la divination dans l’antiquité, Tome II, Éditeur Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1880, p.149

xxivA. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire de la divination dans l’antiquité, Tome II, Éditeur Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1880, p.160

xxvZeus is begotten by his mother and nourished by the milk of his nurse, which can be represented by this diagram: (Cybèle) = Rhéa → Zeus ← Sibylle = (Almathéa)

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.