God needs men, even more than men need God.

The theurgic, creative power of men has always manifested itself through the ages.

Religious anthropology bears witness to this.

« No doubt, without the Gods, men could not live. But on the other hand, the Gods would die if they were not worshipped (…) What the worshipper really gives to his God is not the food he puts on the altar, nor the blood that flows from his veins: that is his thought. Between the deity and his worshippers there is an exchange of good offices which condition each other. »i

The Vedic sacrifice is one of the most ancient human rite from which derives the essence of Prajāpati, the supreme God, the Creator of the worlds.

« There are rites without gods, and there are rites from which gods derive ».ii

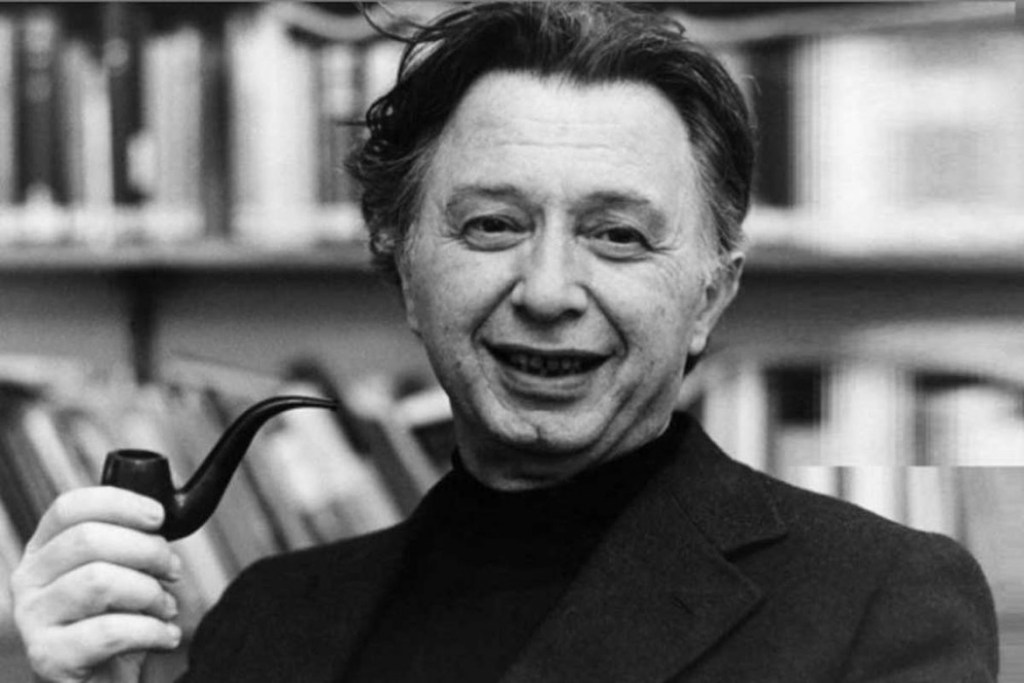

Unexpectingly, Charles Mopsik, in his study of the Jewish kabbalah, subtitled The Rites that Make God, affirms the « flagrant similarity » of these ancient theurgical beliefs with the Jewish motif of the creative power of the rite.

Mopsik readily admits that « the existence of a theme in Judaism, according to which man must ‘make God’, may seem incredible.»iii

Examples of Jewish kabbalistic theurgy abound, involving, for example, man’s ‘shaping’ of God, or his participation in the ‘creation’ of the Name or the Shabbath. Mopsik evokes a midrash quoted by R. Bahya ben Acher, according to which « the man who keeps the Shabbath from below, ‘it is as if he were doing it from above’, in other words ‘gave existence’, ‘fashioned the Sabbath from above. »iv

The expression ‘to make God’, which Charles Mopsik uses in the subtitle of his book, can be compared to the expression ‘to make the Shabbath’ (in the sense of ‘to create the Shabbath’) as it is curiously expressed in the Torah (« The sons of Israel will keep the Shabbath to make the Shabbath » (Ex 31,16)), as well as in the Clementine Homilies, a Judeo-Christian text that presents God as the Shabbath par excellencev, which implies that ‘to make the Shabbath’ is ‘to make God’…

Since its very ancient ‘magical’ origins, theurgy implies a direct relationship between ‘saying’ and ‘doing’ or ‘making’. The Kabbalah takes up this idea, and develops it:

« You must know that the commandment is a light, and he who does it below affirms (ma’amid) and does (‘osseh) that which is above. Therefore, when man practices a commandment, that commandment is light.»vi

In this quotation, the word ‘light’ is to be understood as an allusive way of saying ‘God’, comments Mopsik, who adds: « Observances have a sui generis efficacy and shape the God of the man who puts them into practice.»

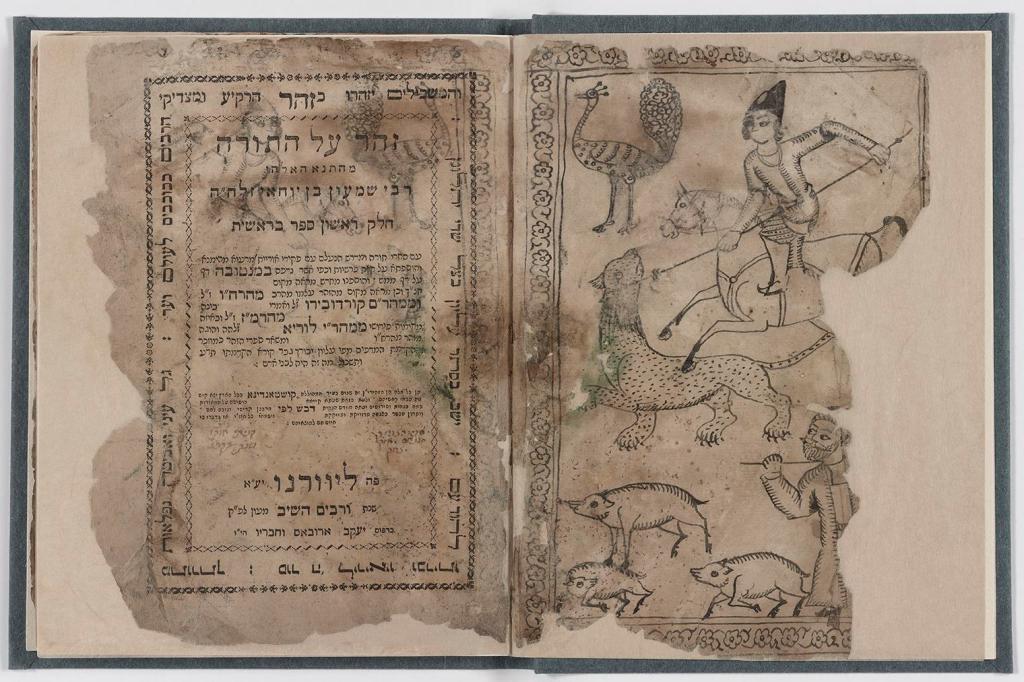

Many other rabbis, such as Moses de Leon (the author of the Zohar), Joseph Gikatila, Joseph of Hamadan, Méir ibn Gabbay, or Joseph Caro, affirm the power of « the theurgic instituting action » or « theo-poietic ».

The Zohar explains :

« ‘If you follow my ordinances, if you keep my commandments, when you do them, etc.' ». (Lev 26:3) What does ‘When you do them’ mean? Since the text already says, « If you follow and keep, » what is the meaning of « When you do them »? Verily, whoever does the commandments of the Torah and walks in its ways, so to speak, it is as if he makes Him on high (‘avyd leyh le’ila), the Holy One blessed be He who says, ‘It is as if he makes Me’ (‘assa-ny). In this connection Rabbi Simeon said, ‘David made the Name’. » vii

« David made the Name » ! This is yet another theurgical expression, and not the least, since the Name, the Holy Name, is in reality God Himself !

‘Making God’, ‘Making the Shabbath’, ‘Making the Name’, all these theurgic expressions are equivalent, and the authors of the Kabbalah adopt them alternately.

From a critical point of view, it remains to be seen whether the kabbalistic interpretations of these theurgies are in any case semantically and grammatically acceptable. It also remains to be ascertained whether they are not rather the result of deliberately tendentious readings, purposefully diverting the obvious meaning of the Texts. But even if this were precisely the case, there would still remain the stubborn, inescapable fact that the Jewish Kabbalists wanted to find the theurgic idea in the Torah .

Given the importance of what is at stake, it is worth delving deeper into the meaning of the expression « Making the Name », and the way in which the Kabbalists understood it, – and then commented on it again and again over the centuries …

The original occurrence of this particular expression is found in the second book of Samuel (II Sam 8,13). It is a particularly warlike verse, whose usual translation gives a factual, neutral interpretation, very far in truth from the theurgic interpretation:

« When he returned from defeating Syria, David again made a name for himself by defeating eighteen thousand men in the Valley of Salt. »

David « made a name for himself », i.e. a « reputation », a « glory », in the usual sense of the word שֵׁם, chem.

The massoretic text of this verse gives :

וַיַּעַשׂ דָּוִד, שֵׁם

Va ya’ass Daoud shem

« To make a name for oneself, a reputation » seems to be the correct translation, in the context of a warlord’s glorious victory. Biblical Hebrew dictionaries confirm that this meaning is widespread.

Yet this was not the interpretation chosen by the Kabbalists.

They prefer to read: « David made the Name« , i.e. « made God« , as Rabbi Simeon says, quoted by the Zohar.

In this context, Charles Mopsik proposes a perfectly extraordinary interpretation of the expression « making God ». This interpretation (taken from the Zohar) is that « to make God » is equivalent to the fact that God constitutes His divine fullness by conjugating (in the original sense of the word!) « His masculine and feminine dimensions ».

If we follow Mopsik, « making God » for the Zohar would be the equivalent of « making love » for both male and female parts of God?

More precisely, as we will see, it would be the idea of YHVH’s loving encounter with His alter ego, Adonaï?

A brilliant idea, – or an absolute scandal (from the point of view of Jewish ‘monotheism’)?

Here’s how Charles Mopsik puts it:

« The ‘Holy Name’ is defined as the close union of the two polar powers of the divine pleroma, masculine and feminine: the sefira Tiferet (Beauty) and the sefira Malkhut (Royalty), to which the words Law and Right refer (…) The theo-poietic action is accomplished through the unifying action of the practice of the commandments that cause the junction of the sefirot Tiferet and Malkhut, the Male and Female from Above. These are thus united ‘one to the other’, the ‘Holy Name’ which represents the integrity of the divine pleroma in its two great poles YHVH (the sefira Tiferet) and Adonay (the sefira Malkhut). For the Zohar, ‘To make God’ therefore means to constitute the divine fullness [or pleroma] by uniting its masculine and feminine dimensions. » viii

In another passage of the Zohar, it is the (loving) conjunction of God with the Shekhina, which is proposed as an equivalence or ‘explanation’ of the expressions « making God » or « making the Name »:

« Rabbi Judah reports a verse: ‘It is time to act for YHVH, they have violated the Torah’ (Ps.119,126). What does ‘the time to act for YHVH’ mean? (…) ‘Time’ refers to the Community of Israel (the Shekhinah), as it is said: ‘He does not enter the sanctuary at all times’ (Lev 16:2). Why [is it called] ‘time’? Because there is a ‘time’ and a moment for all things, to draw near, to be enlightened, to unite as it should be, as it is written: ‘And I pray to you, YHVH, the favourable time’ (Ps 69:14), ‘to act for YHVH’ [‘to make YHVH’] as it is written: ‘David made the Name’ (II Sam 8:13), for whoever devotes himself to the Torah, it is as if he were making and repairing the ‘Time’ [the Shekhinah], to join him to the Holy One blessed be He. » ix

After « making God », « making YHVH », « making the Name », here is another theurgical form: « making Time », that is to say « bringing together » the Holy One blessed be He and the Shekhina…

A midrach quoted by R. Abraham ben Ḥananel de Esquira teaches this word attributed to God Himself: « Whoever fulfills My commandments, I count him as if they had made Me. » x

Mopsik notes here that the meaning of the word ‘theurgy’ as ‘production of the divine’, as given for example in the Liturgy, may therefore mean ‘procreation’, as a model for all the works that are supposed to ‘make God’. xi

This idea is confirmed by the famous Rabbi Menahem Recanati: « The Name has commanded each one of us to write a book of the Torah for himself; the hidden secret is this: it is as if he is making the Name, blessed be He, and all the Torah is the names of the Saint, blessed be He. » xii

In another text, Rabbi Recanati brings together the two formulations ‘to make YHVH’ and ‘to make Me’: « Our masters have said, ‘Whoever does My commandments, I will count him worthy as if he were making Me,’ as it is written, ‘It is time to make YHVH’ (Ps 119:126)xiii.

One can see it, tirelessly, century after century, the rabbis report and repeat the same verse of the psalms, interpreted in a very specific way, relying blindly on its ‘authority’ to dare to formulate dizzying speculations… like the idea of the ‘procreation’ of the divinity, or of its ‘begetting’, in itself and by itself….

The kabbalistic image of ‘procreation’ is actually used by the Zohar to translate the relationship of the Shekhina with the divine pleroma:

« ‘Noah built an altar’ (Gen 8:20). What does ‘Noah built’ mean? In truth, Noah is the righteous man. He ‘built an altar’, that is the Shekhina. His edification (binyam) is a son (ben) who is the Central Column. » xiv

Mopsik specifies that the ‘righteous’ is « the equivalent of the sefira Yessod (the Foundation) represented by the male sexual organ. Acting as ‘righteous’, the man assumes a function in sympathy with that of this divine emanation, which connects the male and female dimensions of the sefirot, allowing him to ‘build’ the Shekhina identified at the altar. » xv

In this Genesis verse, we see that the Zohar reads the presence of the Shekhina, represented by the altar of sacrifice, and embodying the feminine part of the divine, and we see that the Zohar also reads the act of « edifying » her, symbolized by the Central Column, that is to say by the ‘Foundation’, or the Yessod, which in the Kabbalah has as its image the male sexual organ, and which thus incarnates the male part of the divine, and bears the name of ‘son’ [of God]…

How can we understand these allusive images? To say it without a veil, the kabbalah does not hesitate to represent here (in a cryptic way) a quasi-marital scene where God ‘gets closer’ to His Queen to love her…

And it is up to ‘Israel’ to ensure the smooth running of this loving encounter, as the following passage indicates:

» ‘They will make me a sanctuary and I will dwell among you’ (Ex 25:8) (…) The Holy One blessed be He asked Israel to bring the Queen called ‘Sanctuary’ to Him (…) For it is written: ‘You shall bring a fire (ichêh, a fire = ichah, a woman) to YHVH’ (Lev 23:8). Therefore it is written, ‘They will make me a sanctuary and I will dwell among you’. » xvi

Let’s take an interested look at the verse: « You will approach a fire from YHVH » (Lev 33:8).

The Hebrew text gives :

וְהִקְרַבְתֶּם אִשֶּׁה לַיהוָה

Ve-hiqravttêm ichêh la-YHVH

The word אִשֶּׁה , ichêh, means ‘fire’, but in a very slightly different vocalization, ichah, this same word means ‘woman’. As for the verb ‘to approach’, its root is קרב, qaraba, « to be near, to approach, to move towards » and in the hiphil form, « to present, to offer, to sacrifice ». Interestingly, and even disturbingly, the noun qorban, ‘sacrifice, oblation, gift’ that derives from it, is almost identical to the noun qerben which means ‘womb, entrails, breast’ (of the woman).

One could propose the following equations (or analogies), which the Hebrew language either shows or implies allusively:

Fire = Woman

Approaching = Sacrifice = Entrails (of the woman)

‘Approaching the altar’ = ‘Approaching a woman’ (Do we need to recall here that, in the Hebrew Bible, « to approach a woman » is a euphemism for « making love »?)

The imagination of the Kabbalists does not hesitate to evoke together (in an almost subliminal way) the ‘sacrifice’, the ‘entrails’, the ‘fire’ and the ‘woman’ and to bring them formally ‘closer’ to the Most Holy Name: YHVH.

It should be noted, however, that the Kabbalists’ audacity is only relative here, since the Song of Songs had, long before the Kabbalah, dared to take on even more burning images.

In the thinking of the Kabbalists, the expression « to make God » is understood as the result of a « union » of the masculine and feminine dimensions of the divine.

In this allegory, the sefira Yessod connects God and the Community of believers just as the male organ connects the male body to the female body. xvii

Rabbi Matthias Delacroute (Poland, 16th century) comments:

« ‘Time to make YHVH’ (Ps 119:126). Explanation: The Shekhinah called ‘Time’ is to be made by joining her to YHVH after she has been separated from Him because one has broken the rules and transgressed the Law. » xviii

For his part, Rabbi Joseph Caro (1488-1575) understood the same verse as follows: « To join the upper pleroma, masculine and divine, with the lower pleroma, feminine and archangelical, must be the aim of those who practice the commandments (…) The lower pleroma is the Shekhinah, also called the Community of Israel ». xix

It is a question of magnifying the role of the Community of Israel, or that of each individual believer, in the ‘divine work’, in its ‘reparation’, in its increase in ‘power’ or even in its ‘begetting’….

Rabbi Hayim Vital, a contemporary of Joseph Caro, comments on a verse from Isaiah and relates it to another verse from the Psalms in a way that has been judged « extravagant » by literalist exegetesxx.

Isaiah’s verse (Is 49:4) reads, according to R. Hayim Vital: « My work is my God », and he compares it with Psalm 68: « Give power to God » (Ps 68:35), of which he gives the following comment: « My work was my God Himself, God whom I worked, whom I made, whom I repaired ».

Note that this verse (Is 49:4) is usually translated as follows: « My reward is with my God » (ou-féoulati êt Adonaï).

Mopsik comments: « It is not ‘God’ who is the object of the believer’s work, or action, but ‘my God’, that God who is ‘mine’, with whom I have a personal relationship, and in whom I have faith, and who is ‘my’ work. »

And he concludes that this ‘God who is made’, who is ‘worked’, is in reality ‘the feminine aspect of the divinity’.

The Gaon Elijah of Vilna proposed yet another way of understanding and designating the two ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ aspects of the Deity, calling them respectively ‘expansive aspect’ and ‘receiving aspect’:

« The expansive aspect is called havayah (being) [i.e. HVYH, anagram of YHVH…], the receiving aspect of the glorification coming from us is called ‘His Name’. In the measure of Israel’s attachment to God, praising and glorifying Him, the Shekhinah receives the Good of the expanding aspect. (…) The Totality of the offices, praise and glorification, that is called Shekhinah, which is His Name. Indeed, ‘name’ means ‘public renown’ and ‘celebration’ of His Glory, the perception of His Greatness. (…) This is the secret of ‘YHVH is one, and His Name is one’ (Zac 14:9). YHVH is one’ refers to the expansion of His will. ‘His Name is one’ designates the receiving aspect of His praise and attachment. This is the unification of the recitation of the Shema.» xxi

According to the Gaon of Vilna, the feminine dimension of God, the Shekhina, is the passive dimension of the manifested God, a dimension that is nourished by the Totality of the praises and glorifications of the believers. The masculine dimension of God is Havayah, the Being.

Charles Mopsik’s presentation on the theurgical interpretations of the Jewish Kabbalah (‘Making God’) does not neglect to recognize that these interpretations are in fact part of a universal history of the religious fact, particularly rich in comparable experiences, especially in the diverse world of ‘paganism’. It is thus necessary to recognize the existence of « homologies that are difficult to dispute between the theurgic conceptions of Hellenized Egyptian hermeticism, late Greco-Roman Neoplatonism, Sufi theology, Neoplatonism and Jewish mystagogy. » xxii

Said in direct terms, this amounts to noting that since the dawn of time, there has been among all ‘pagan’ people this idea that the existence of God depends on men, at least to a certain degree.

It is also striking that ideas seemingly quite foreign to the Jewish religion, such as the idea of a Trinitarian conception of God (notoriously associated with Christianity) has in fact been enunciated in a similar way by some high-flying cabbalists.

Thus the famous Rabbi Moses Hayim Luzzatto had this formula surprisingly comparable (or if one prefers: ‘isomorphic’) to the Trinitarian formula:

« The Holy One, Blessed be He, the Torah and Israel are one. »

But it should also be recalled that this kind of « kabbalistic » conception has attracted virulent criticism within conservative Judaism, criticism which extends to the entire Jewish Kabbalah. Mopsik cites in this connection the outraged reactions of such personalities as Rabbi Elie del Medigo (c. 1460- 1493) or Rabbi Judah Arie of Modena (17th century), and those of equally critical contemporaries such as Gershom Scholem or Martin Buber…

We will not enter into this debate. We prefer here to try to perceive in the theurgic conceptions we have just outlined the clue of an anthropological constant, an archetype, a kind of universal intuition proper to the profound nature of the human spirit.

It is necessary to pay tribute to the revolutionary effort of the Kabbalists, who have shaken with all their might the narrow frames of old and fixed conceptions, in an attempt to answer ever-renewed questions about the essence of the relationship between divinity, the world and humanity, the theos, the cosmos and the anthropos.

This titanic intellectual effort of the Jewish Kabbalah is, moreover, comparable in intensity, it seems to me, to similar efforts made in other religions (such as those of a Thomas Aquinas within the framework of Christianity, around the same period, or those of the great Vedic thinkers, as witnessed by the profound Brahmanas, two millennia before our era).

From the powerful effort of the Kabbalah emerges a specifically Jewish idea of universal value:

« The revealed God is the result of the Law, rather than the origin of the Law. This God is not posed at the Beginning, but proceeds from an interaction between the superabundant flow emanating from the Infinite and the active presence of Man. » xxiii

In a very concise and perhaps more relevant way: « You can’t really know God without acting on Him, » also says Mopsik.

Unlike Gershom Scholem or Martin Buber, who have classified the Kabbalah as « magic » in order to disdain it at its core, Charles Mopsik clearly perceives that it is one of the signs of the infinite richness of human potential in its relationship with the divine. We must pay homage to him for his very broad anthropological vision of the phenomena linked to divine revelation, in all eras and throughout the world.

The spirit blows where it wants. Since the dawn of time, i.e. for tens of thousands of years (the caves of Lascaux or Chauvet bear witness to this), many human minds have tried to explore the unspeakable, without preconceived ideas, and against all a priori constraints.

Closer to us, in the 9th century AD, in Ireland, John Scot Erigenes wrote:

« Because in all that is, the divine nature appears, while by itself it is invisible, it is not incongruous to say that it is made. » xxiv

Two centuries later, the Sufi Ibn Arabi, born in Murcia, died in Damascus, cried out: « If He gave us life and existence through His being, I also give Him life, knowing Him in my heart.» xxv

Theurgy is a timeless idea, with unimaginable implications, and today, unfortunately, this profound idea seems almost incomprehensible in our almost completely de-divinized world.

___________________

iE. Durckheim. Elementary forms of religious life. PUF, 1990, p.494-495

iiE. Durckheim. Elementary forms of religious life. PUF, 1990, p. 49

iiiCharles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.551

ivIbid.

vClementine Homilies, cf. Homily XVII. Verdier 1991, p.324

viR. Ezra de Girona. Liqouté Chikhehah ou-féah. Ferrara, 1556, fol 17b-18a, cited in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.558

viiZohar III 113a

viiiCharles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.561-563.

ixZohar, I, 116b, cited in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites which make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.568

xR. Abraham ben Ḥananel de Esquira. Sefer Yessod ‘Olam. Ms Moscow-Günzburg 607 Fol 69b, cited in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.589

xiSee Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.591

xiiR. Menahem Recanati. Perouch ‘al ha-Torah. Jerusalem, 1971, fol 23b-c, quoted in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites which make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.591

xiiiR. Menahem Recanati. Sefer Ta’amé ha-Mitsvot. London 1962 p.47, cited in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites which make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.591

xivZohar Hadach, Tiqounim Hadachim. Ed. Margaliot. Jerusalem, 1978, fol 117c quoted in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites which make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.591

xvCharles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.593

xviR. Joseph de Hamadan. Sefer Tashak. Ed J. Zwelling U.M.I. 1975, p.454-455, cited in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites which make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p.593

xviiSee Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p. 604

xviiiR. Matthias Délacroute. Commentary on the Cha’aré Orah. Fol 19b note 3. Quoted in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites which make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p. 604

xixCharles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p. 604

xxIbid.

xxiGaon Elijah of Vilna. Liqouté ha-Gra. Tefilat Chaharit, Sidour ha-Gra, Jerusalem 1971 p.89, cited in Charles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites which make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p. 610

xxiiCharles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p. 630

xxiiiCharles Mopsik. The great texts of the cabal. The rites that make God. Ed. Verdier. Lagrasse, 1993, p. 639

xxivJean Scot Erigène. De Divisione Naturae. I,453-454B, quoted by Ch. Mopsik, Ibid. p.627

xxvQuoted by H. Corbin. The creative imagination

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.