A « Deep Dive » Podcast on « Psyche and Death » :

Psyche and Death

The word ψυχὴ, psyche, has as its root : Ψυχ, “to blow”. This etymology explains the primary meaning of psyche, as given in dictionaries: « breath of life ». From this vital breath derive the other meanings: « soul, life, soul as the seat of feelings, intelligence and desires ». But in Homer, the word psyche only appears at the moment of death, when the breath exhales and escapes the body. The psyche then heads for Hades, taking on the appearance of an « image » resembling the dead, unable to assume any of the functions of the living body, except that of speaking with the living. As we have seen, for Homer, the thumos or phrenes embodied certain forms of human consciousness during life. The psyche represents consciousness during and after death. When Eniopeus, driver of Hector’s chariot, dies, « he feels both his psyche and his forces exhalei. » When Pandarus dies, « his psyche and his strength are exhaledii. » Sarpedon’s death coincides with the joint escape, from the body, of the psyche and his life: « As soon as his psyche and his life (αἰών, aiōn) have abandoned himiii « . When Hyperenor dies, the psyche flees through the wound: « His psyche rushed impetuously through that gaping wound, and the darkness of death (Σκότος, skotos) covered his eyesiv. » The psyche can also escape from the body along with the entrails or lungs: « Patroclus, leaning his foot on Sarpedon’s chest, withdraws the spear from the body. The phrenes (lungs) escape through the wound. The hero rips out both Sarpedon’s psyche and the iron of his spearv. » Death has no return: « The soul of man does not return, either by pillage or by capture, when it escapes from the barrier of teethvi « .

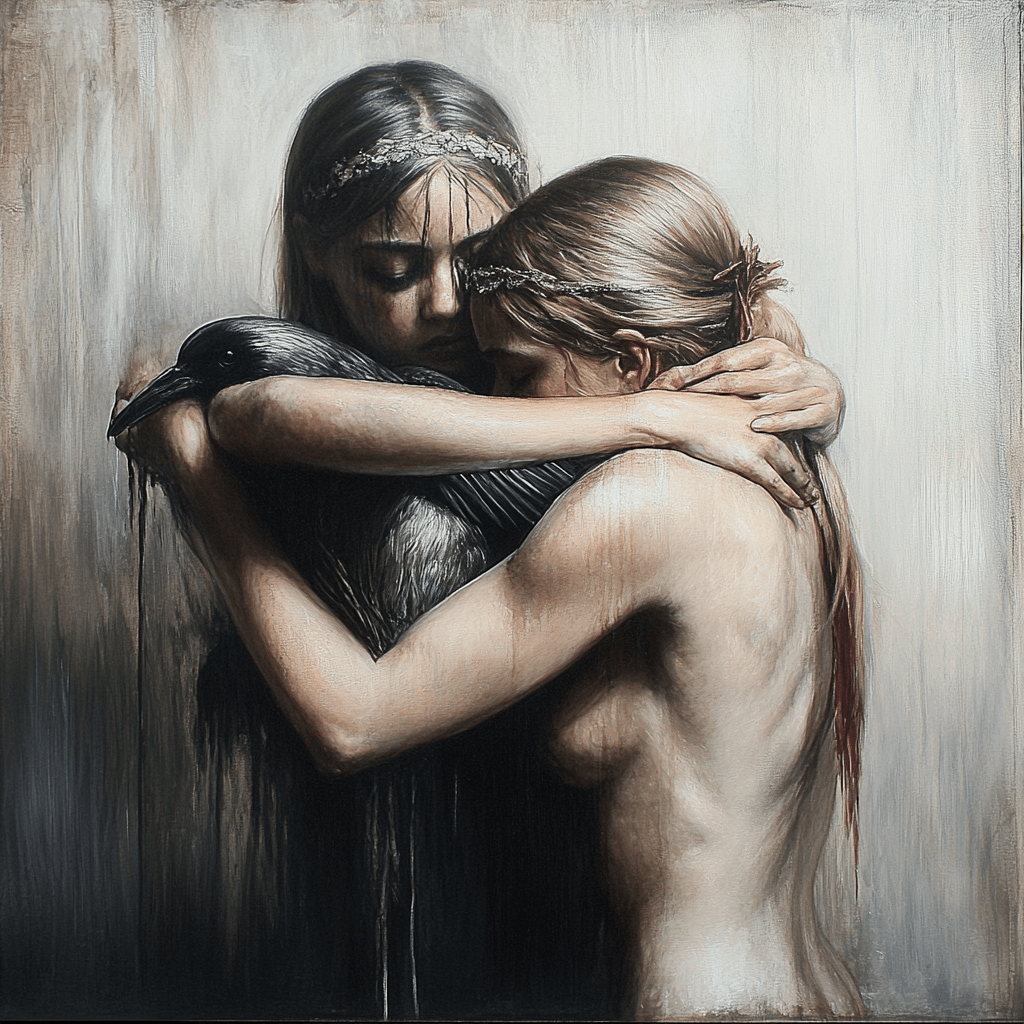

The essential characteristic of the psycheis to sur-vive after death, and to descend into Hades. It therefore does not die, even if Homer sometimes uses the expression « death of the psyche« . Hector is completely covered in the rich bronze armor of which he stripped Patroclus after immolating him. However, a small opening remains at the precise point where, near the throat, the bone separates the neck from the shoulder, and the Poet says that one finds « there, the quicker death of the psychevii « . This is also where Achilles strikes Hector with his spear. But when Hector dies, his psyche doesn’t « die », as announced a few verses earlier, it « flies away »: « His psyche, far from the body, flies off to Hadesviii « . If the psyche flies to Hades, this does not necessarily mean that it can enter and reside there with the other dead. A key scene in the Iliad reunites Achilles with the psyche of Patroclus, who died without a grave and was therefore prevented from entering Hades. One night, the psyche of the Patroclus appears to Achilles. It appears in the form of an image (eidōlon), and is in his likeness: his height, his eyes, his voice, and the same clothes with which he was clothed. He approaches Achilles’ head, and asks him to raise a pyre for him, then prepare a grave where his bones can be reunited with Achilles’ after his own death. Achilles wants to embrace his friend one last time, but he cannot grasp Patroclus’ shadow, whose soul escapes moaning « into the bosom of the earth (κατὰ χθονὸς, kata chthonos) like smoke (καπνὸς), uttering an inarticulate cry (τετριγυῖα)ix « . Achilles stands up, and in a mournful voice, draws some precise, analytical conclusions from what he has just seen: « Great heavens! the soul (psyche) or at least its image (εἴδωλον, eidōlon) thus exists in the abodes of Hades, when the phrenes are absolutely not there. All through the night, the soul of the unfortunate Patroclus appeared to me moaning and plaintive; she prescribed all his commands to me, and she looked marvelously like him! ». What Achilles has just understood is part of teachings handed down over the centuries, the essence of which can be summed up as follows: when death occurs, it is the psyche that survives and flees to the realm of Hades and Persephone. Then, if the funeral honors have been paid and the corpse burned to the ground, it detaches itself for good from the world of the living and sinks into the darkness of Erebus, into the Chthonic depths. Once in Hades, the psyche of the dead is invisible to the living. But the psyche of the living is also invisible. Its presence in the body remains elusive throughout life: it only really reveals itself at the moment of death, when it separates from the body. So, how do we represent this elusive entity? Paradoxically, it only becomes « visible » when it is still wandering between the world of the living and the realm of the « Invisible » (which is the meaning of the word « Hades« ), and it’s still in this in-between situation.

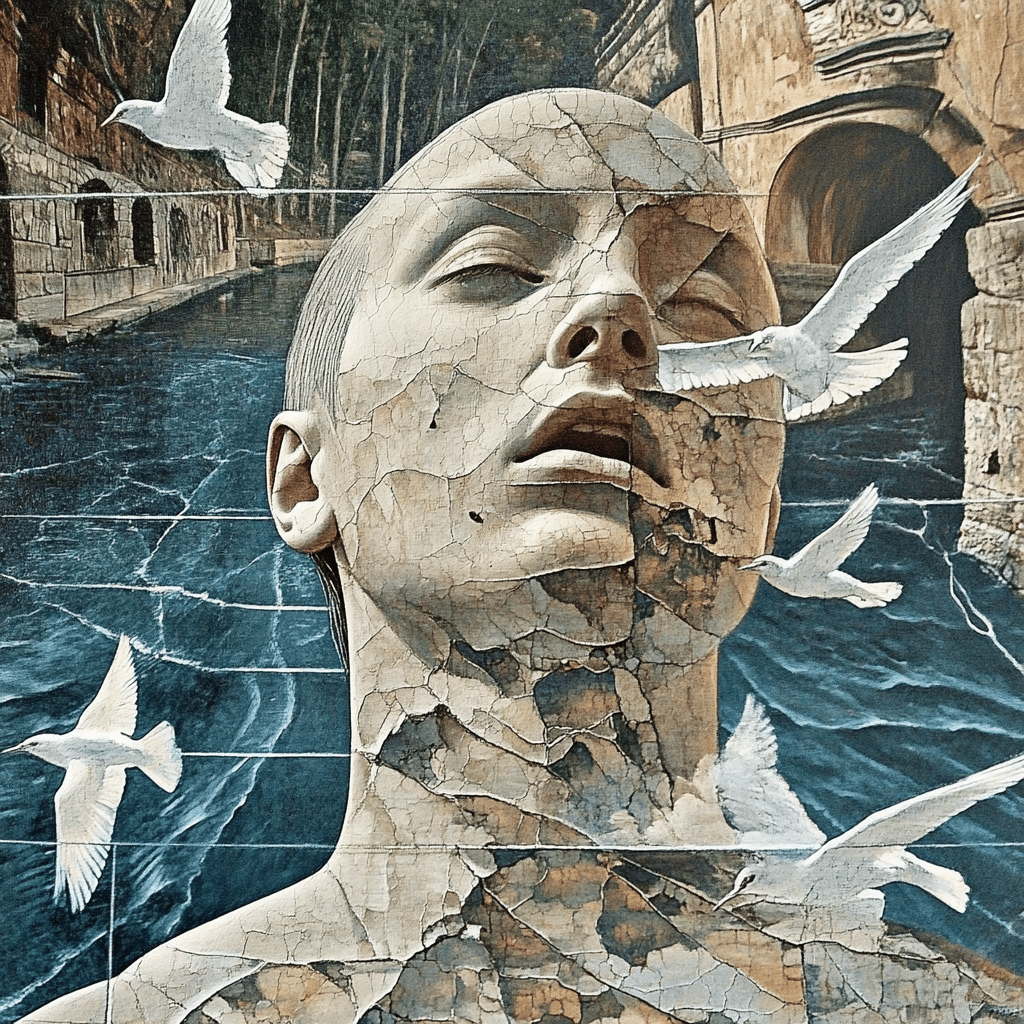

The word psyche, like the Latin word anima, refers to « breath », which can be felt rather than seen, and which is revealed indirectly through breathing. At death, the psyche escapes through the mouth, or through the gap of a wound. In this new freedom, it flees into the Invisible, taking the form of an « image » (εἴδωλον, eidōlon), which has the impalpable consistency of smokex and the appearance of night. In Hades, the soul, or rather its eidōlon, its image, is described as being « like the dark nightxi « . However, to this smoke, to this shadow, to this night, to this image, can still be attributed intelligence, spirit. The psyche of a dead man can receive the noos: « For, even dead, Persephone has left him alone the intelligence (noos); the others are but a flight of shadowsxii « .

The psyche may have the noos, but it is not itself ‘spirit’: « The Homeric psyche in no way resembles what, as opposed to the body, we usually call ‘spirit’xiii. » The usual functions of the human mind are only possible during life. At death, the body and its organs disintegrate, along with the mind and intellectual faculties. The psyche remains intact, but has lost all knowledge. « All the energies of the will, all sensibility, all thought disappear when man returns to the elements of which he was composedxiv. «

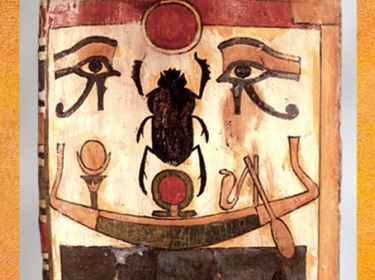

The spirit of the living man needs the psyche, but the psyche, when in Hades, performs none of the functions of the spiritxv. Without the psyche, the body can no longer perceive, feel, think or will. But it is not the psyche within the body, let alone outside it, that can exercise these functions. Descended into Hades, the psyche is referred to in the Iliad and Odyssey by the name of the man from whom it sprang, and the poet attributes to it the appearance and personality of the once- living self.From this we can infer that, according to Homeric conception, man has a dual existence, one in his visible, embodied form, and the other as an invisible « image ». For Homer, the psycheis a kind of silent double, a second self, which inhabits the body during life, only revealing itself to the living after death, in a few cases, and then only very briefly. This Greek concept is by no means exceptional: it also corresponds to the ka of the Egyptians, the genius of the Romans and the fravaschi of the Persians. The idea of a double self, one sensitive and visible, the other latent and hidden, may well have appeared long ago, before the dawn of history, under the influence of dreams, but also of the ecstatic transports and out-of-body experiences that shamans and all those who have undergone initiation rites accompanied by the absorption of psychotropic drugs, in all eras and all regions of the world. This idea has also been reinforced by the sharing of near-death experiences (NDEs), which must have been as frequent in ancient times as they are today.

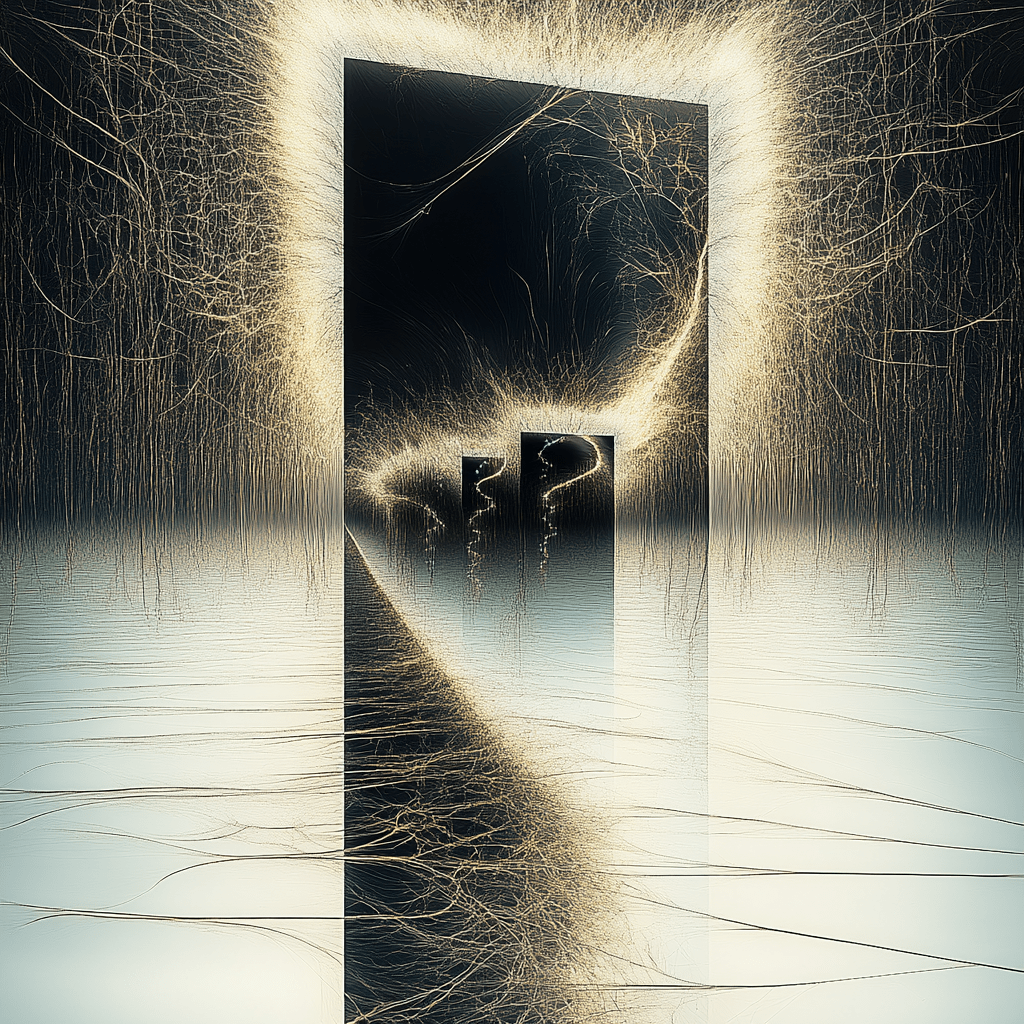

If the psyche corresponds to the presence of another, invisible self, surviving after death, the questions multiply… What is the origin of the psyche? What is the origin of the psyche‘s ability to survive after death, to live on in another life, in the depths of Hades? The first ancient Greek to assert the divine origin of the psyche, and thus explain its immortality, was Pindar. « The body obeys death, the almighty. But the image [of time] of life (αἰῶνος εἲδωλον, aiōnoseidōlon) remains alive (ζωὸν, zōon), for it alone derives its origin from the gods (τὸ γάρ ἐστι μόνον ἐκ θεῶν). She sleeps as long as the limbs are in motion, but she often announces in a dream the future to the one who sleepsxvi. » This living image (eidōlon zōon) of what was alive during the time of life (aiōnos) is the psycheitself.It is that psychic « double » that is embedded in every human being, and undetectable until death comes. It is the psyche that ‘remains alive’ after the death of the body, for it alone comes from the gods (ek theōn), deriving its origin from a divine gift. In the full version of this fragment by Pindar, we find an allusion to the essential role of initiation into the Mysteries, in terms of the psyche‘s chances of survival after death, and especially of its subsequent participation in divine life, and all its gifts. « Happy are those who have received an initiation (teletan) that delivers them from the pangs of death (lusiponon). Their bodies are tamed by the death that drags them along. Only their psyche remains alive, for it comes to them from the gods. This shadow sleeps while our limbs act; but often, during sleep, it shows us in a dream the punishments and rewards that the decrees of the gods have in store for us after our deathxvii. » John Sandys translates the word αἴσα in this fragment as « the fruit (of the rite) ». The rite, which delivers us from the torments of death, has as its « fruit » access to eternal lifexviii. But the word αἴσα actually means not the « fruit », but « the lot that Destiny assigns to each person ». It is therefore not the reward for effort, but a free gift of divinity to those who have successfully undergone initiation. As for the « rite » of initiation (teletàn), it corresponds to that accompanying the celebration of the Eleusis mysteries. Those who remain uninitiated as to the knowledge of sacred things (ἀτελὴς ἱερῶν), will not have the happy fate of the initiated, when faced with death.

Another fragment of Pindar, dedicated to the Mysteries of Eleusis, lifts a corner of the veil on the meaning of initiation. « Blessed is he who has seen them [the Mysteries of Eleusis] before descending beneath the earth, for he knows the outcome of life; he knows the principle of the gift of Godxix « . There is some ambiguity as to the exact nature of the « gift » given by Zeus to the initiates. Is it a spiritual gift, an illumination, a revelation of the very principle and essence of ‘what is given’ by Zeus, or is it, more prosaically, dare I say it, the gift of ‘new life’? Moreover, in this fragment, the word arkhê retains its dual meaning of « principle » and « beginning ». The fragment suggests that happy is the one who « sees » (or understands) the « principle » (arkhê) of the « divine gift » (diodotos) as it reveals itself in the « beginning » (arkhê) of a new life (after death).

In another fragment, Pindar says that the psyche « sleeps » when the body is in motion. While it sleeps, it may invisibly seek out intuitions, visions or elements of consciousness, which will transpire underground and appear to the consciousness of the waking person, or which may later nourish future dreams, when the person is plunged into sleep (and the psyche can freely exert its influence). So the psyche apparently has no role in the waking activities of consciousness, but perhaps exerts its influence through dreams and the unconscious? The psyche seems to live in a second world, parallel to the common world. When a person is awake, the psyche sleeps. But when the person is asleep, the psyche is awake, acting as a second, unconscious self. What it perceives in dreams are not chimeras, hollow dreams, pure daydreams, but realities of a higher order. They are divine realities, or fleeting images (eidōla) that the gods consent to send to man. Among these is the reality of the psyche‘s life after death, which is revealed as self-evident. Achilles had this experience in a dream, and it appeared to him as a true revelation of the survival of Patroclus’ soul, and proof of its very real existence in the realm of shadows. « As he said these words, Achilles held out his hands, but he could not grasp them, and the soul in the bosom of the earth, like light smoke, shuddered away. Achilles immediately rises, claps his hands loudly, and, in a mournful voice, cries out: ‘Great gods! so the soul (psyche) and its image (eidōlon) exist in the abodes of Hades, when the phrenes are absolutely not there’xx. » Achilles, in his dream, discovers the truth of the continued life of Patroclus’ soul, even though the latter is absolutely (πάμπαν) deprived of his phrenes, whose essential role as receptacle of breath and thumoswe have seen. As a warrior, Achilles is well aware that his own spirit can easily faint, for example following a violent blow, which can bring him to the brink of death, without necessarily then dreams coming to reassure him, or visions of the beyond assailing him. In Homer’s language, this type of fainting is expressed in phrases like « the psyche has abandoned the bodyxxi« . So where does the psyche go when it abandons the body? We don’t really know, but we do know that when it returns, it finds the body’s phrenes, with which it assembles and unites once more. In true death, the psycheleaves the body for good, never to return. Just as the psyche was unaffected by its momentary departures during life, and may have benefited from certain visions where appropriate, so we can reasonably assume (from the point of view of Homeric culture) that upon actual death, it will not be annihilated, but will continue to survive (to over–live).

Certainly going back to ancient soul cults, the Greek belief, as expressed in the Iliad and Odyssey, was that after death, the psyche « descends into Hadesxxii » — but not immediately. Seemingly indecisive, it « flies », hesitating for a while longer, wandering between the world of Hades and the realm of the dead. It is only when funeral honors have been paid to the dead, and the body burned at the stake, that the psyche can definitively pass through the gates of Hades. In fact, this is what Patroclus’ psyche asks of Achilles when it appears to him at night: « You sleep, Achilles, and forget me. You never neglected me during my life, and you forsake me after my death; celebrate my funeral promptly, so that I may pass through the gates of Hades. Souls (psyche), images of those who have finished suffering, push me away, and do not allow me beyond the river to mingle with them; and it is in vain that I wander around the dwelling with the vast gates of Hades: stretch out to me, I beseech you, a helping hand. Alas! I shall return no more from Hades when you have granted me the honors of the pyrexxiii. » Patroclus’ psyche had flown to Hades, unable to pass through its gates. Likewise, the psyche of Odysseus’ companion Elpenor has descended into Hades, without actually entering. He remains in an in-between world. Fortunately for him, Elpenor is the first psyche Ulysses encounters on his visit to the people of the dead. Elpenor begs Odysseus to burn his body with all his weapons, and give him a proper burialxxiv. In both Patroclus’ and Elpenor’s cases, the psyche has not lost its self-awareness. It is able to speak with the living, and implore them to burn the unburied corpse of which it is the psyche. It can argue, for as long as the psyche remains attached to the earth by a bodily bond, even that of a decomposing corpse, it still has some awareness of what’s going on with the living, and a capacity for reasoning. A scholiast, Aristonicos, commenting on the Iliad, clearly states that, for Homer, the souls of those deprived of burial still retain their consciousnessxxv. When the body has been reduced to ashes, the psyche finally enters Hades, with no possible return to the world of the living, or communication with them. It no longer perceives the slightest breath, the slightest thought coming from the world above (the world of the living), nor does its thought return to earth. All ties are severed. The only exception is Achilles. He vows to always remember Patroclus, his companion who died without a grave, and whose psyche,unable to penetrate Hades, is condemned to wander endlessly. Achilles asserts that he will never forget Patroclus, not only while he is alive, but also when he himself is in Hades, among the deadxxvi. For the psyche, death is nothing, since love transcends it. For heroes capable of love, like Achilles, death may indeed be nothing. But we still have to think about it.

Long after Homer, the wise and stoic Seneca, speaking of his asthma which made him suffer, declared that his attacks gave him the feeling of approaching the ultimate experience of death: « To have asthma is to give up the spirit. That’s why doctors call it a death meditation. This lack of breathing does in the end what it has tried many times […] During my suffocation, I did not let myself be consoled by sweet and strong thoughts. What is this? I said to myself; death often puts me to the test; let it do as it pleases, I’ve known it for a long time. But when? you may ask: before I was born; for to be nothing is to be dead: I know what that is now. It will be the same after me as it was before mexxvii. » Whether suffering from the mourning of a loved one, or suffocating asthma, the lessons of Homer and Seneca are comparable: we must meditate ceaselessly on both death and the psyche. It’s the same mystery.

i Iliad 8,123

ii Iliad 5,296

iii Iliad 16,453

iv Iliad 14, 518

v Iliad 16,504-505

vi Iliad 9, 408-9

vii Iliad 22,325

ix Iliad 23,100

x Iliad 23,100

xi Odyssey 11,606

xii Odyssey 10,495-6

xiii Erwin Rohde. Psyche.The cult of the soul among the Greeks and their belief in immortality. Ed. Les Belles Lettres. 2017, p. 3

xiv Ibid.

xv Ibid:« Man is only alive, self-conscious and intellectually active as long as the psycheremains within him, but it is not the psyche that, through the communication of its own energies, ensures man’s life, self-consciousness, will and knowledge. »

xvi Pindar, fragment131. Ibid. p. 5

xvii C. Poyard. Complete translation of Pindar. Imprimerie impériale. Paris, 1853, p. 245-246. Poyard’s translation in French reads: « Tous, par un sort heureux, arrivent au terme qui les délivre des maux de la vie ». The translator seems to read in Pindar’s text the word teleutê, ‘term, accomplishment, realization’, whereas it actually reads the accusative singular (teletan) of the word teletê, ‘ceremony of initiation, celebration of the mysteries, rites of initiation’.

xviii Pindar. The Odes of Pindar including the Principal Fragments.Fragment 131. Trad. John Sandys. Ed. William Heinemann. London, 1915, p.589

xix C. Poyard. Complete translation of Pindar. Imprimerie impériale. Paris, 1853, p. 247. I have slightly modified this translation. « The outcome of life »:τελευτὰν, teleutan.« He knows what the outcome of life is »: οἶδεν μὲν βιοτου τελευτὰν. « The principle »: ἀρχάν, arkhan.« God’s gift »: δ ι ό σ δ ο τ ο ν , diosdoton « He knows the principle of God’s gift »: οἶδεν δὲ διόσδοτον ἀρχάν. I choose to translate arkhan as « principle ». I n other translations, the phrase diosdoton arkhan (διόσδοτον ἀρχάν) is translated as « the beginning [of a new life] given by Zeus ». John Sandys translates as follows: « Blessed is he who hath seen these things before he goeth beneath the earth; for he understandeth the end of mortal life, and the beginning (of a new life) given of god. » (Pindar. The Odes of Pindar including the Principal Fragments. Fragment 137. Trad. John Sandys. Ed. William Heinemann. London, 1915, p.591-593)

xx Iliad 23, 103-107. Achilles’ exclamation in the Greek text: ὢ πόποι ἦ ῥά τίς ἐστι καὶ εἰν Ἀΐδαο δόμοισι ψυχὴ καὶ εἴδωλον, ἀτὰρ φρένες οὐκ ἔνι πάμπαν-

xxi Iliad 5, 696-697: « His soul abandoned him, but he regained his breath ». Iliad 22, 466-467: When Hecuba sees her dead husband Hector: « The dark night veiled her eyes completely, she fell backwards, and exhaled her soul far away ». But this escape of the soul does not last… Iliad 22, 475: « When she had caught her breath (empnutō), and her spirit (thumos) had gathered in her phrenes. » I have taken this set of quotations from Erwin Rohde’s book. Psyche. The cult of the soul among the Greeks and their belief in immortality. French translation by Auguste Reymond. Ed. Les Belles Lettres. 2017, p. 6 note 3.

xxii Iliad16,856: « No sooner [Patroclus] finished these words, than he is enveloped in the shadows of death; his soul flying from his body descends into Hades, and laments his fate by abandoning strength and youth. »

xxiii Iliad 23, 71-76

xxiv Odyssey 10, 560 and 11, 51-83

xxv Quoted by E. Rohde, op.cit. p.21, note 1

xxvi Iliad 22,389: « Alas! before the ships, deprived of our tears and of burial, lies lifeless Patroclus’ corpse. No, I’ll never forget him as long as I’m among the living, and my knees can move. If among the dead, in the bosom of the underworld, we lose all memory, me, I will still keep the memory of my faithful companion. »

xxvii Seneca. Letters to Lucilius,54

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.