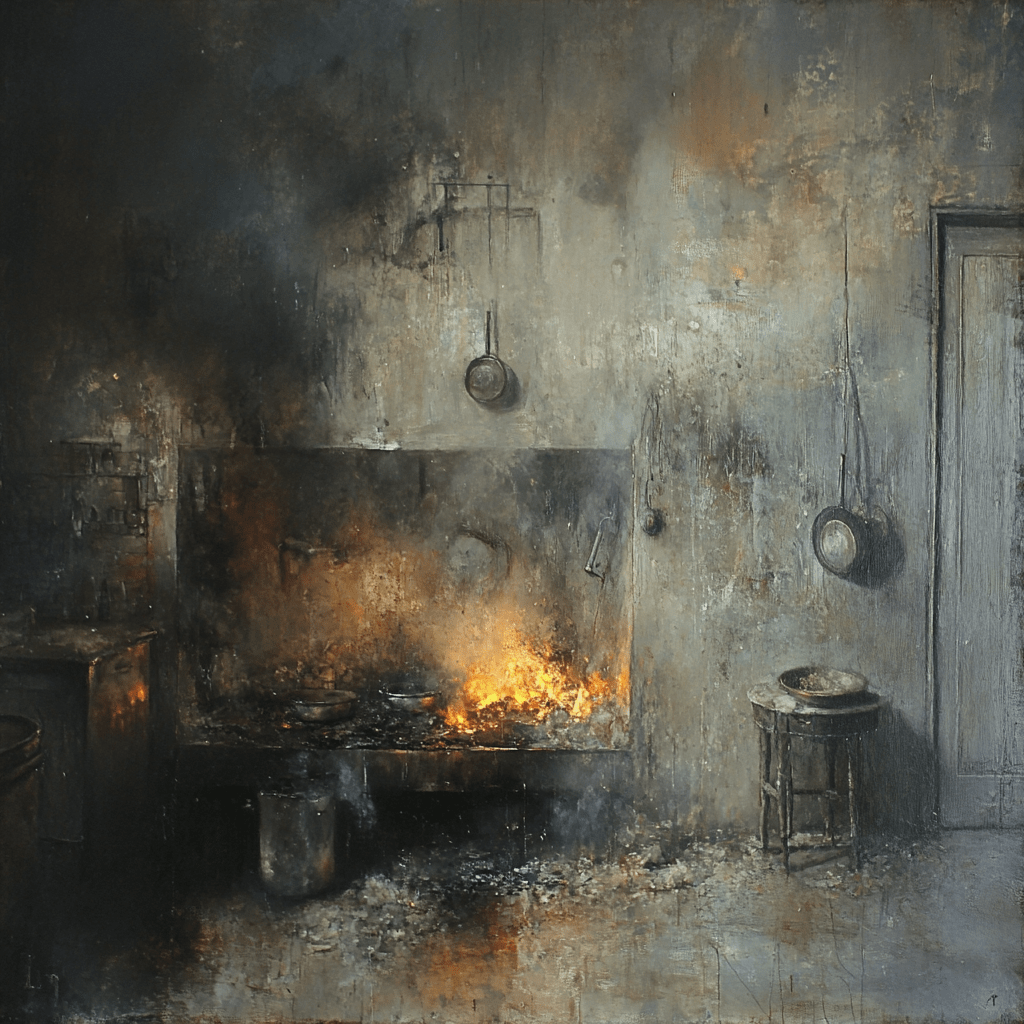

When you are alone in winter, when night has fallen, when everything is dark and quiet, sometimes all you can see within yourself are scattered, disconnected thoughts. You add up or subtract the years, we weigh up the long series of events that mercilessly remind us how much time has passed, we measure the slow and irresistible approach of the final darkness, which we may think will engulf everything we love, everything we possess, everything we desire and hope for, everything towards which our life’s efforts have tended. Our consciousness takes on the appearance of a dark cave, undetectable from the surface of the world, in which all kinds of thoughts, fleeting or profound, seem to huddle together, as if they wanted to flee the light of day. Then this insidious fear can arise, the fear of having failed, of not having understood anything, of having missed the truth. It envelops the soul in a heavy, sticky, clinging cloud. The soul then rebels, wanting to rise towards the sky, towards the sun, towards summer, and fly in the crisp, rare air of the peaks.

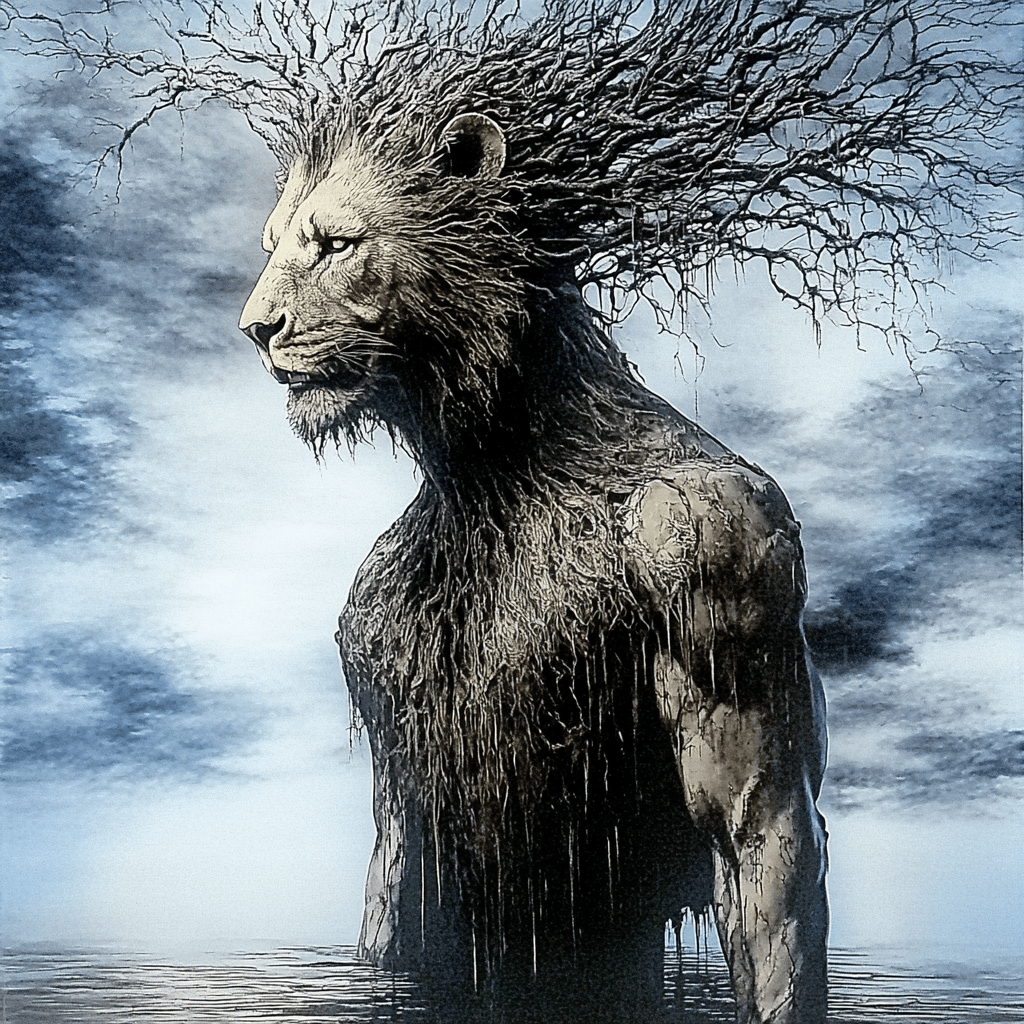

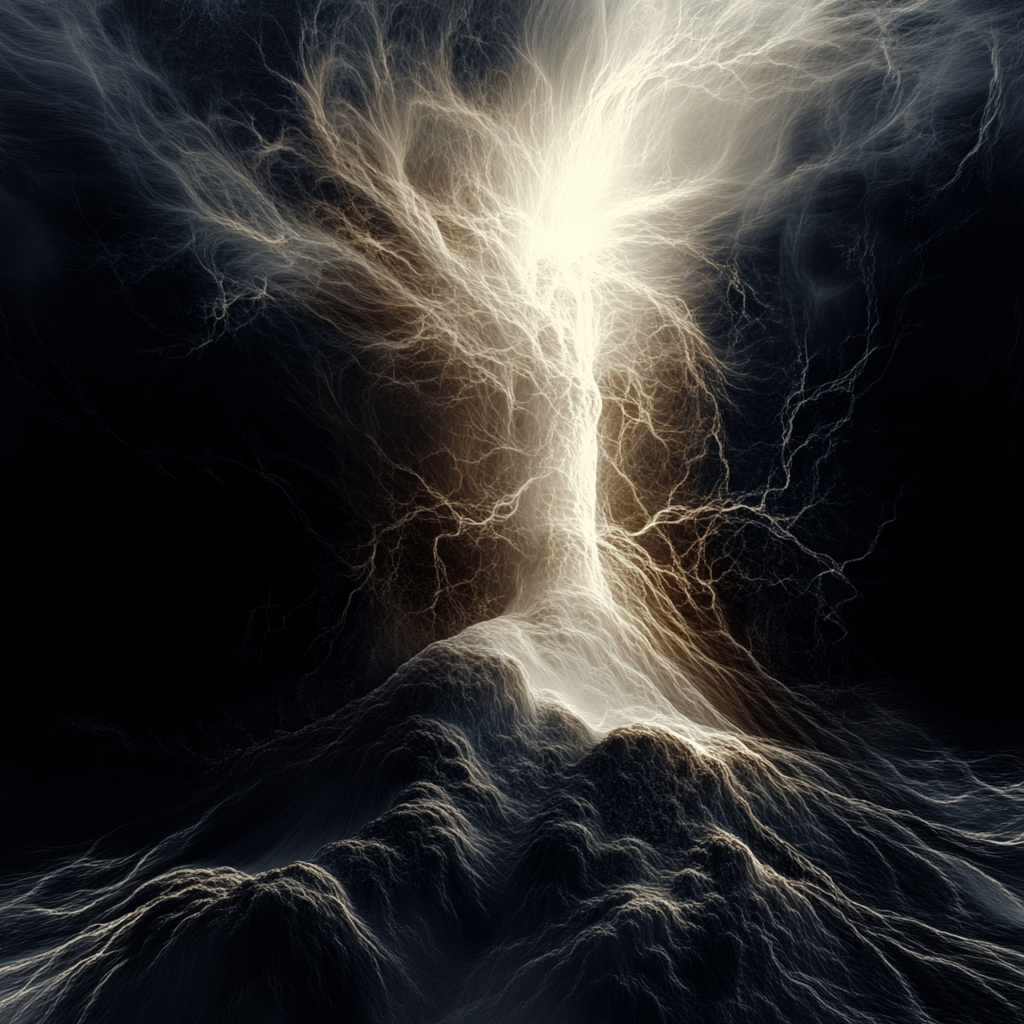

Life is a movement, an energetic process. It consumes energy (material and spiritual) and also produces it (without us knowing according to what equations of equivalence or transformation). The important question for any individual consciousness is to assess what the ultimate outcome will be, i.e. over the long and even very long term. Like any energetic process, life follows a course that is in principle irreversible; but if we assume that infinity cannot exist in a finite world, all life is necessarily oriented towards its « end », in both senses of the term – the end as a « terminus », precisely, and the end as « meaning ». These two meanings, it should be noted, are in fact potentially contradictory, insofar as an ‘end’ puts an end to ‘meaning’ (of what preceded the ‘end’, on the one hand, and, conversely, any realisation of ‘meaning’ potentially opens up other paths that were previously unthought of and even unthinkable. The « end » of life, according to materialist analyses, would represent a « state of rest », to use a euphemism, or a state of maximum entropy (to borrow a concept from thermodynamics). In the long term, according to the thermodynamic point of view, everything that happens over time is the result of an initial disturbance arising within a state of rest that is a priori perpetual, but which, in this case, gives way to a disturbed state, and then constantly attempts to re-establish a new, more or less definitive state of rest. From a more philosophical point of view, life is teleological par excellence; its telos, or « end », is the intrinsic search for its end (no pun intended), the immanent effort towards its goal, whatever that may be. All living organisms are constantly organising themselves according to objectives that are supposed to enable them to achieve this telos, this very immanent goal. But this definition of life obviously has the disadvantage of being self-referential. If the end of the process is its goal, and if its goal is its end, what place is there for a transcendent telos, which would be above or outside these categories, that of finitude or even that of « finality »? Natural life is fertile ground for the soul; it is the very humus of the human soul. The soul follows the course of life to grow at its own pace, to learn all its movements, and, having assimilated them in part, to finally begin to dance to its own rhythm, in all the moments when it flows quickly, or more slowly but with amplitude, to accompany the symphony to its conclusion. This is why age does not measure a real, unique state of consciousness. Only the entire score of a life could give an idea of the movements of transformation of consciousness that, at any age, are yet to come. But does this score even exist? Isn’t it constantly being developed? This is why consciousness, caught up in the flow of the music of existence, must not look back and cling to notes already played and chords already struck. It must continue to play its part without fear. From the middle of life onwards, only those who become aware of their finitude, only those who are ready to die with life, remain truly alive. At this strange hour in the middle of life, a turning point is reached, the curve is reversed, and death comes into clearer perspective. The second half of life does not mean ascension, fulfilment, growth, exuberance, but slowdown, decline, detachment and finally death, since the end is its goal. The denial of the fulfilment of life is synonymous with the refusal to accept its end. Both are equivalent to not wanting to die, and therefore not wanting to live. Growth and decline are part of the same curve. And as Taylor’s series teach us, it should be possible to derive the curve at a single point, but with all its derivatives to infinity, in order to be able to calculate its future inflections, which would otherwise be inconceivable.

A young-at-heart septuagenarian, isn’t that wonderful? And yet, that is not enough. He must also know how to listen to the secret murmurs of streams, imagine the slopes he has descended, the glaciers left up there near the peaks, but also the bubbling of the tributaries in the valleys, the slow, riverine pace of the basins, and finally the mystery of ocean immersions. In fact, regardless of age, no one really knows what their own « soul » is. We know just as little about how it manifests itself in nature. And we know absolutely nothing about its origin or its true « end ». The facts and « truths » that can be drawn from physical reality are limited to matter and nature. But is the soul physical and material in nature, or metaphysical and spiritual? All we can say, reasoning by analogy, is that a psychic or spiritual ‘truth’ is in principle just as valid and respectable as a physical ‘truth’. All that remains is to identify the world in which this type of psychic truth could exercise its validity. Is it in this world, the world of matter and nature? Or are other worlds possible? The question is obviously open. The key point is that only death can provide an answer (or a non-answer) to this question.

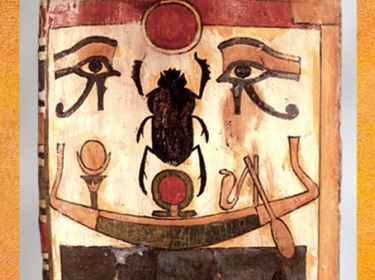

Thoughts of death become increasingly pressing as the years go by. Whether we like it or not, ageing means preparing for death. Nature itself shows us every day that we must prepare for the end. Objectively speaking, what each individual consciousness may think about death is irrelevant. Death is an invariant. It introduces a symmetry break between two states, life and ‘death’. To use the notation bra < | and ket | > introduced by Paul Dirac in quantum mechanics, and if we denote « life » by φ, the formula <φ|…> differs intrinsically from <…|φ> or even from <φ|…|φ>, and it differs even more from <φ|… |ϠΛΦ |…| ΞϔΘϪ>. The … here symbolise our ignorance of what follows death and the break it introduces, symbolised by |. As for the capital letters Ϡ Λ Φ Ξ ϔ Θ Ϫ i, they symbolise other concepts to which I will return later i. Subjectively, there is a huge difference between a consciousness that willingly and sincerely accompanies the rhythm of life until death and a consciousness that clings to artificial opinions about the meaning of life and its supposed opposite, death. It is just as neurotic in old age not to focus on the approaching prospect of death as it is in youth not to let oneself be overwhelmed by the intoxication of possibilities and the future. Jung says somewhere that he was surprised to see how little importance the « unconscious psyche » attaches to death. It would seem that death represents something relatively insignificant for it. Perhaps the psyche does not care what happens to the individual? It would essentially be linked to the collective unconscious, and therefore to the future and the « end » of the total, collective psyche. It also seems that the « psyche » specific to a particular person is interested in how that person feels about the prospect of death: it is more concerned with whether the attitude of consciousness is appropriate to the reality of death than with death itself. From this point of view, the fact that a singular consciousness is totally incapable of imagining another form of existence, in a world devoid of space and time, in no way proves that such an existence is impossible in itself. We cannot draw any absolute conclusions about the reality or unreality of forms of existence outside this space-time (in Riemann’s sense), i.e. outside this world. We are not entitled to deduce, based on the quality of our perceptions and our spatio-temporal intuitions in this life, that no other forms of existence exist, for example in types of space that are no longer spatio-temporal, but in spaces that could be described as « noetic » or « spiritual ». Drawing inspiration from models commonly used in quantum chromodynamics, and from metaphors such as that of the « quantum vacuum » discussed in my article The Void and the Soul, it is not only permissible to doubt the absolute validity of the spatio-temporal perceptions associated with this world, but it is even imperative to do so, given the available facts and advances in science. In other words, the quantum world, which is very much part of « reality », also reveals all the limitations of the spatio-temporal conceptions of Riemannian space-time. The hypothesis that the psyche is linked to forms of existence outside Riemannian space-time raises scientific questions that deserve serious consideration. The conceptual apparatus of quantum chromodynamics would allow this to be done within a rigorous framework, which has been validated by numerous empirical experiments. I do not mean to say that quantum chromodynamics itself holds the answer to philosophical or spiritual questions. I simply wish to express the idea that it offers an excellent learning tool for the development of more general, broader and perhaps more universal frameworks of thought, and that this movement towards greater generality and universality could also be put to good use in more creative and inventive philosophical and spiritual questioning. From a philosophical point of view, the existence and unity of a particular Riemannian space-time structure, with its singularity but also its « limits », means that the very concept of space-time must be relativised. If I wish to take advantage of the creative freedom offered by this « relativity », I could then imagine that death in this world, in this Riemannian space-time called « cosmos », actually allows us to translate ourselves into another world, no longer composed of lengths, widths and depths (x, y, z), but endowed with transcendental dimensions denoted by Ϡ, Λ, Φ, or, even more surprisingly, of dimensions without dimensions, denoted by Ξ, ϔ, Θ, Ϫ. This world could also be seen as a chaos-cosmos-noos-theos, whose virtualities, intricately intertwined to the fourth power, would be essentially and eternally « unaccomplished » (in the sense of the « unaccomplished » or « imperfect » mode of Hebrew grammar, as particularly highlighted in Ex. 3:14).

The nature of the psyche extends into areas of darkness that are far beyond our understanding. It conceals more enigmas than the universe with its nebulae, galactic clusters and black holes. This extreme weakness of human understanding regarding the nature of the psyche makes the materialistic, positivist and intellectualist hubbub not only ridiculous, but also deplorably boring. So, in accordance with the impulses of the ancient lessons of human wisdom, and taking into account the psychological fact that religious ‘revelations’, brilliant ‘intuitions’ and ‘telepathic’ perceptions have already occurred and been observed in reality, one would be perfectly justified in concluding that the psyche, in its most unfathomable depths, also participates in a form of existence beyond space and time, within a chaos-cosmos-noos-theos quaternion, to which critical reason could not oppose any a priori argument, any more than it can deny the emergence, within the quantum vacuum, of « virtual » particles with nevertheless very « real » effects.

____________________

iThey are read respectively as Ϡ sampi, Λ lambda, Φ phi, Ξ xi, ϔ upsilon (with diaeresis), Θ theta and Ϫ gangia (the first six are Greek, the last is Coptic). They symbolise consciousness, ecstasy, love, sacrifice, ecstasy, the divine, and transcendence.

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.