Ancient languages, such as Sanskrit, Egyptian, Avestic, Chinese, Hebrew and Greek, possess a kind of secret spirit, an immanent soul, which makes them develop as living powers, often without the knowledge of the people who speak them, and could be compared to insects foraging in a forest of words, with fragrant, autonomous and fertile scents.

This phenomenal independence of languages from the men who speak and think with them is the sign of a mystery, latent from their genesis. « Languages are not the work of a reason conscious of itself”, wrote Turgoti .

They are the work of another type of ‘reason’, a superior one, which could be compared to the putative reason of language angels, active in the history of the world, haunting the unconscious of peoples, and drawing their substance from them, just as much as from the nature of things.

The essence of a language, its DNA, lies in its grammar. Grammar incorporates the soul of the language. It represents it in all its potency, without limiting its own genius. Grammar is there but it is not enough to explain the genius of the language. The slow work of epigenesis, the work of time on words, escapes it completely.

This epigenesis of the language, how can it be felt? One way is to consider vast sets of interrelated words, and to visit through thought the society they constitute, and the history that made them possible.

Let’s take an example. Semitic languages are organized around verbal roots, which are called « trilitera » because they are composed of three radical letters. But these verbs (concave, geminated, weak, imperfect, …) are not really « triliterated ». To call them so is only « grammatical fiction », Renan assertedii. In reality, triliteral roots can be etymologically reduced to two radical, essential letters, the third radical letter only adding a marginal nuance.

For example, in Hebrew, the two root letters פר (para) translate the idea of ‘separation’, ‘cut’, ‘break’. The addition of a third radical letter following פר then modulates this primary meaning and gives a range of nuances: פרד parada « to separate, to be dispersed », פרח paraha « to erupt, to germinate, to blossom », פרס parasa « to tear, to split », פרע para’a « to reject, to dissolve », פרץ paratsa « to destroy, to cut down, to break », פרק paraqa « to break, to tear », פרס perasa « to break, to share », פרש parasha « to break, to disperse ».

The keyboard of possible variations can be further expanded. The Hebrew language allows the first radical letter פ to be swapped with the beth ב, opening up other semantic horizons: ברא bara « to create, to draw from nothing; to cut, to cut down », ברה bara’a « to choose », ברר barada « to hail », בבח baraha, « to flee, to hunt », ברך barakha, « to bless; to curse, to offend, to blaspheme », ברק baraqa, « to make lightning shine », ברר barara, « to separate, sort; to purify ».

The Hebrew language, which is very flexible, may also allow permutations with the second letter of the verbal root, changing for example the ר by צ or by ז. This gives rise to a new efflorescence of nuances, opening up other semantic avenues:

פצה « to split, to open wide », פצח « to burst, to make heard », פצל « to remove the bark, to peel », פצם « to split, to open in », פצע « to wound, to bruise », בצע « to cut, to break, to delight, to steal », בצר « to cut, to harvest », בזה « to despise, to scorn », בזא « to devastate », בזר « to spread, to distribute », בזק « lightning flash », בתר « to cut, to divide ».

Through oblique shifts, slight additions, literal « mutations » and « permutations » of the alphabetic DNA, we witness the quasi-genetic development of the words of the language and the epigenetic variability of their meanings.

Languages other than Hebrew, such as Sanskrit, Greek or Arabic, also allow a thousand similar discoveries, and offer lexical and semantic shimmering, inviting us to explore the endless sedimentation of the meanings, which has been accumulating and densifying for thousands of years in the unconscious of languages.

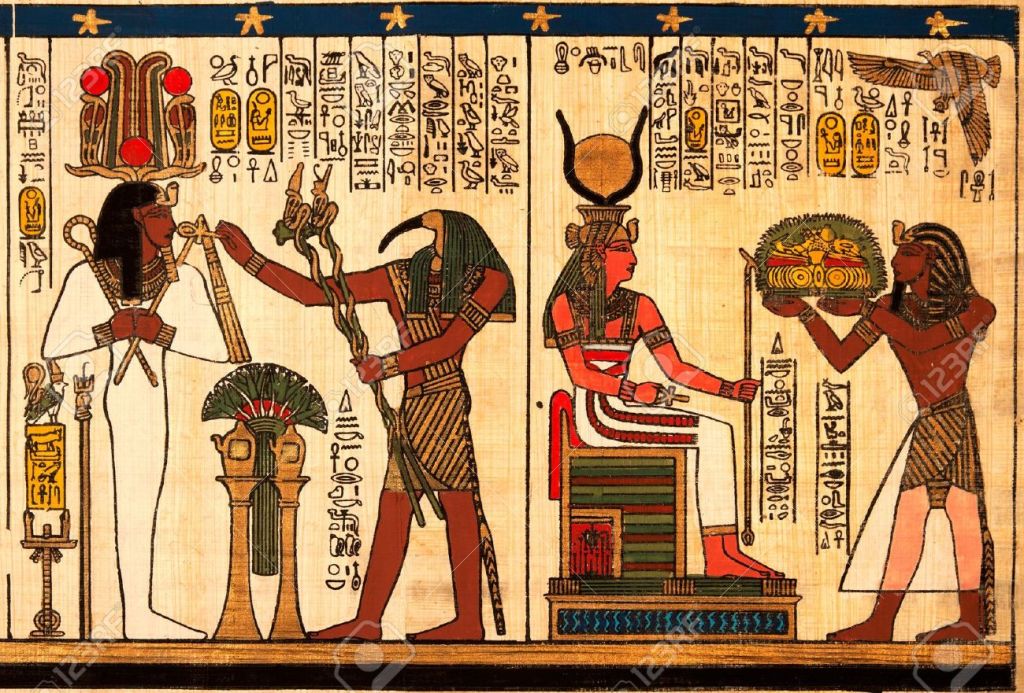

In contrast, the Chinese language or the language of ancient Egypt do not seem to have a very elaborate grammar. On the other hand, as they are composed of monosyllabic units of meaning (ideograms, hieroglyphics) whose agglutination and coagulation also produce, in their own way, myriads of variations, we then discover other generative powers, other specific forms generating the necessary proliferation of meaning.

Grammar, lexicography and etymology are sometimes poetic, surprising and lively ways of accessing the unconscious of language. They do not reveal it entirely, however, far from it.

A psychoanalysis of language may reveal its unconscious and help finding the origin of its original impulses.

For example, it is worth noting that the language of the Veda, Sanskrit – perhaps the richest and most elaborate language ever conceived by man – is almost entirely based on a philosophical or religious vocabulary. Almost all entries in the most learned Sanskrit dictionaries refer in one way or another to religious matters. Their network is so dense that almost every word naturally leads back to them.

One is then entitled to ask the question: Is (Vedic) religion the essence of (Sanskrit) language? Or is it the other way round? Does Vedic language contain the essence of Veda?

This question is of course open to generalization: does Hebrew contain the essence of Judaism? And do its letters conceal an inner mystery? Or is it the opposite: is Judaism the truth and the essence of the Hebrew language?

In a given culture, does the conception of the world precede that of language? Or is it the language itself, shaped by centuries and men, which ends up bringing ancient religious foundations to their incandescence?

Or, alternatively, do language and religion have a complex symbiotic relationship that is indistinguishable, but prodigiously fertile – in some cases, or potentially sterile in others? A dreadful dilemma! But how stimulating for the researcher of the future.

One can imagine men, living six or twelve thousand years ago, possessing a penetrating intelligence, and the brilliant imagination of a Dante or a Kant, like native dreamers, contemplating cocoons of meaning, slow caterpillars, or evanescent butterflies, and tempting in their language eternity – by the idea and by the words, in front of the starry night, unaware of their ultimate destiny.

iTurgot. Remarques sur l’origine des langues. Œuvres complètes . Vol. 2. Paris, 1844. p.719

iiErnest Renan. De l’origine du langage. 1848

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.