In archaic and classical Greece, the art of divination, the art that deals with everything « that is, that will be and that was »,i was considered knowledge par excellence. In Plutarch’s On the E of Delphi,ii Ammonios says that this knowledge belongs to the domain of the gods, and particularly to Apollo, the master of Delphi, the God called ‘philosophos’. The sun, reputed to see and know everything and illuminate whoever it wished, was merely his symbol, and Apollo, son of Zeus, was really the mantic God in essence. However, at Delphi, another son of Zeus, Dionysus, was also involved in the art of mantics, competing with Apollo in this field.iii Dionysus, ever-changing, multi-faceted and ecstatic, was the opposite and complementary type of Apollo, who was the image of the One, equal to himself, serene and immobile.

In Homeric Greece, an augur like Calchas tried to hear divine messages by distinguishing and interpreting signs and clues in the flight of birds or the entrails of sacrificial animals. He sought to discover and interpret what the Gods were willing to reveal about their plans and intentions. But, at Delphi, the divinatory art of Dionysus and Apollo was of a very different nature. It was no longer a question of looking for signs, but of listening to the very words of the God. Superhuman powers, divine or demonic, could reveal the future in the words of the Greek language, in cadenced hexameters. These powers could also act without intermediaries in the souls of certain men with special dispositions, enabling them to articulate the divine will in their own language. These individuals, chosen to be the spokespersons of the Gods, could be diviners, sibyls, the « inspired » (entheoi), but also heroes, illustrious figures, poets, philosophers, kings and military leaders. All these inspired people shared one physiological characteristic, the presence in their organs of a mixture of black bile, melancholikè krasisiv .

In Timaeus, Plato distinguished in the body a « kind of soul » which is « like a wild beast » and which must be « kept tied to its trough » in « the intermediate space between the diaphragm and the border of the navel »v. This « wild » soul, placed as far as possible from the rational, intelligent soul, the one that deliberates and judges free from passions, is covered by the liver. The ‘children of God’, entrusted by God ‘the Father’‘vi with the task of begetting living mortals,vii had also installed the ‘organ of divination’ in the liver, as a form of compensation for the weakness of human reason. « A sufficient proof that it is indeed to the infirmity of human reason that God has given the gift of divination: no man in his right mind can achieve inspired and truthful divination, but the activity of his judgement must be impeded by sleep or illness, or diverted by some kind of enthusiasm. On the contrary, it is up to the man of sound mind, after recalling them, to gather together in his mind the words uttered in the dream or in the waking hours by the divinatory power that fills with enthusiasm, as well as the visions that it has caused to be seen; to discuss them all by reasoning in order to bring out what they may mean and for whom, in the future, the past or the present, bad or good. As for the person who is in the state of ‘trance’ and who still remains there, it is not his role to judge what has appeared to him or been spoken by him (…). It is for this reason, moreover, that the class of prophets, who are the superior judges of inspired oracles, has been instituted by custom; these people are themselves sometimes called diviners; but this is to completely ignore the fact that, of enigmatic words and visions, they are only interpreters, and in no way diviners, and that ‘prophets of divinatory revelations’ is what would best suit their name. »viii

Human reason may be « infirm », but it is nonetheless capable of receiving divine revelation. Soothsayers, oracles, prophets or visionaries are all in the same boat: they must submit to the divine will, which may give them the grace of a revelation, or deny it to them.

Plutarch refers to the fundamental distinction Homer makes between soothsayers, augurs, priests and other aruspices on the one hand, and on the other, the chosen few who are allowed to speak directly with the gods. « Homer seems to me to have been aware of the difference between men in this respect. Among the soothsayers, he calls some augurs, others priests or aruspices; there are others who, according to him, receive knowledge of the future from the gods themselves. It is in this sense that he says:

« The soothsayer Helenus, inspired by the gods,

Had their wishes before his eyes.

Then Helenus said: ‘Their voice was heard by me’. »

Kings and army generals pass on their orders to strangers by signals of fire, by heralds or by the sound of trumpets; but they communicate them themselves to their friends and to those who have their confidence. In the same way, the divinity himself speaks to only a small number of men, and even then only very rarely; for all the others, he makes his wishes known to them by signs that have given rise to the art of divination. There are very few men whom the gods honour with such a favour, whom they make perfectly happy and truly divine. Souls freed from the bonds of the body and the desires of generation become genies charged, according to Hesiod, with watching over mankind ».ix

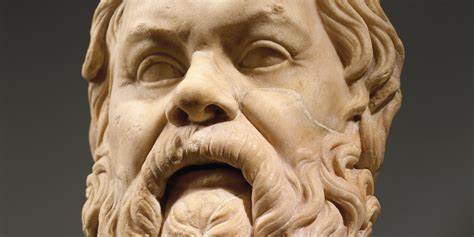

How did the divinity reveal itself? There is a detailed description of how Socrates received the revelation. According to Plutarch, Socrates’ demon was not a ‘vision’, but the sensation of a voice, or the understanding of some words that struck him in an extraordinary way; as in sleep, one does not hear a distinct voice, but only believes one hears words that strike only the inner senses. These kinds of perceptions form dreams, because of the tranquillity and calm that sleep gives the body. But during the day, it is very difficult to keep the soul attentive to divine warnings. The tumult of the passions that agitate us, the multiplied needs that we experience, render us deaf or inattentive to the advice that the gods give us. But Socrates, whose soul was pure and free from passions and had little to do with the body except for indispensable needs, easily grasped their signs. They were probably produced, not by a voice or a sound, but by the word of his genius, which, without producing any external sound, struck the intelligent part of his soul by the very thing it was making known to him.x So there was no need for images or voices. It was thought alone that received knowledge directly from God, and fed it into Socrates’ consciousness and will.xi

The encounter between God and the man chosen for revelation takes the form of an immaterial colloquy between divine intelligence and human understanding. Divine thoughts illuminate the human soul, without the need for voice or words. God’s spirit reaches the human spirit as light reflects on an object, and his thoughts shine in the souls of those who catch a glimpse of that light.xii Revelation passes from soul to soul, from spirit to spirit, and in this case, from God to Socrates: it came from within the very heart of Socrates’ consciousness.

_______________

iAs the augur Calchas said, in Iliad I, 70

iiPlutarch, On the E of Delphi, 387b-c.

iiiMacrobius, Sat. 1, 18, quoted by Ileana Chirassi Colombo, in Le Dionysos oraculaire, Kernos, 4 (1991), p. 205-217.

ivRobert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, Oxford, 1621 (Original title: The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptoms, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up)

vTimaeus, 70e-72b

viTimaeus, 71d

viiTimaeus, 69b-c

viiiTimaeus, 71e-72b

ixPlutarch. » On the Demon of Socrates » 593c-d. Moral Works. Translation from the Greek by Ricard. Tome III , Paris, 1844, p.115-116

xIbid, p.105

xi« But the divine understanding directs a well-born soul, reaching it by thought alone, without needing an external voice to strike it. The soul yields to this impression, whether God restrains or excites its will; and far from feeling constrained by the resistance of the passions, it shows itself supple and manageable, like a rein in the hands of a squire. » Plutarch. « On the Demon of Socrates », Moral Works. Translation from the Greek by Ricard. Tome III , Paris, 1844, p.105

xii« This movement by which the soul becomes tense, animated, and, through the impulse of desires, draws the body towards the objects that have struck the intelligence, is not difficult to understand: the thought conceived by the understanding makes it act easily, without needing an external sound to strike it. In the same way it is easy, it seems to me, for a superior and divine intelligence to direct our understanding, and to strike it with an external voice, in the same way that one mind can reach another, in much the same way as light is reflected on objects. We communicate our thoughts to each other by means of speech, as if groping in the dark. But the thoughts of demons, which are naturally luminous, shine on the souls of those who are capable of perceiving their light, without the use of sound or words ». Ibid, p.106

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.