The Psalmist sang of YHVH’s eternal, irrevocable covenant with David, his servant, his saint, his anointed. But why is he so bitter? He blames YHVH for his sudden breach of that covenant, his unilateral fickleness, his unpredictable anger. « And yet you have forsaken him, rejected him, your chosen one; you have raged against him. You have broken the covenant of your servant, you have degraded him, and thrown down his diadem259. » Wouldn’t the Psalmist be mistaken in his judgment? How could a God so One, so high, so powerful, be unfaithful to his own word? How could an eternal God be understood, let alone judged, by a fleeting creature, however inspired? Besides, if the Psalmist’s bitterness were to be justified, God forbid, wouldn’t it be better not to insist on this broken covenant, this broken promise? No power, whatever it may be, likes to be called into question, and even less to be challenged on its own ground, in this case that of the word and the promise. YHVH, it’s a fact, doesn’t like man’s critical thinking, this nothingness, to be exercised towards Him. Criticism tends to diminish the quality of the homage and praise He expects from His creatures. His power pervades the universe. His essence is eternal, of course. His existence is real, to be sure. However, this ‘power’ and this ‘existence’ only have real meaning if other, non-divine consciousnesses are aware of them, and praise Him for them. Without them, divine ‘power’ would remain self-centered, solipsistic, centripetal, in a way ‘selfish’, or at least ‘egotistical’. And, by the same token, would it not reveal a ‘lack’ within the divine? To make up for this ‘lack’, there is a kind of intrinsic necessity for other consciousnesses to come and fill it, and for some of them to be able to freely recognize the ‘power’ at work, as a condition of existence, of life, of all forms of consciousness. This is why we can infer that the Creator, in His omnipotence, which is supposed to be absolute, felt the desire to create consciousnesses other than His own; He needed singular consciousnesses to « be », other than in Himself. This was the reason for the original, implicit, natural, structural alliance of God with His Creation, the dialectical alliance of uncreated Consciousness with created consciousness.

In the beginning, it was important for His wisdom to be aware of the existence and essence of all the kinds of consciousness that could be created, in the entire Cosmos, until the end of times that may have no end. Now, it’s important for Him, at every moment, to be aware of the meaning that consciousnesses give to themselves. It also matters to Him what meaning they give (or don’t give) to His existence. He obviously wouldn’t have sent prophets down here if He didn’t care. What matters to Him above all is the general movement of consciousness in the world. By means of a thought experiment, a dream of created consciousness, we could imagine that the Creator creates new consciousnesses, which are, in essence, always ‘in the making’, and which must, while alive, be fulfilled. Placed in the world, they bring to life, grow (or shrink) their potential for consciousness, their wills, their desires, their hopes. We could also imagine that the life of these created consciousnesses, the fulfillment of these ephemeral wills, is not unrelated to the fulfillment of uncreated Consciousness, the realization of the eternal will, the Life of the Self. Finally, we could hypothesize that the Creator has, in consciousness, desired the existence of created consciousnesses, and that His desire grows as consciousness grows in the created world. In His unconscious awareness, or in His conscious unconsciousness, the Creator seems almost oblivious to who He really is, why He creates, and how His creative power can be apprehended, understood and praised by His creatures, in principle reasonable, but surprised to be there. On the one hand, if the Scriptures are to be believed, God YHVH seems to have needed to ally Himself exclusively with a people, binding them to Himself with irrevocable promises and eternal oaths. But on the other hand, again according to the Scriptures, God YHVH did not hesitate to break these promises and oaths, for reasons that are not always clear or expressly alleged. He unilaterally broke the covenant with his chosen one, his anointed, even though it had been proclaimed eternal. Terrible consequences are to be expected from this rupture and abandonment: walls demolished, fortresses ruined, populations devastated and plundered, enemies filled with joy, the end of royal splendor, the throne thrown down, and general shame. Woe and suffering now seem destined to last with no foreseeable end, while man’s life is so brief260. What has become of the promise once made, which in principle was to bind the God YHVH for ever261? The conclusion is abrupt, brief, but without acrimony. Finally, twice, the word amen is addressed to this incomprehensible and, it seems, forgetful God: « Praise the Lord forever! Amen and amen262! » The forsaken anointed one, a little disenchanted, doesn’t seem to hold it against the Lord for not having kept his promise. He doesn’t seem eager to insist on this unilateral abandonment, this abolished covenant. He doesn’t want to admit to himself that this gives him a kind of de facto moral advantage over a God who shows himself unaware of his « forgetfulness », whereas he, the chosen one, the anointed one, has forgotten nothing of the promise. Is it out of prudence? In all His glory and power, the God YHVH doesn’t really seem to appreciate criticism when it comes against Him, and even less when it comes from men who are notoriously so fallible, so sinful. Although his power extends across the universe, and no doubt far beyond, God YHVH needs to be ‘known’ and ‘recognized’ by reflective (and laudatory) consciousnesses. He shows his desire to do more than just « being ». He also wants to « exist » for consciousnesses other than His own. Without human, living, attentive consciousnesses that recognize His « existence », God’s « Being » would have no witness other than Himself. In the absence of these free consciousnesses, capable of recognizing His existence and praising His glory, this very existence and this very glory would in fact be literally « absent » from the created world.

The existence of the divine principle could certainly be conceived in absolute unity and solitude. After all, this is how we conceive of the primordial, original God, before Creation came into being. But does the idea of divine ‘glory’ even make sense, if there is no other consciousness to witness it? In essence, any real glory requires conscious glorification by a glorifying multitude, dazzled, conquered, sincere. Could God be infinitely ‘glorious’ in absolute solitude, in the total absence of any ‘presence’, in a desert empty of all ‘other’ consciousnesses capable of perceiving and admiring His glory? He could, no doubt—but not without that glory suffering a certain ‘lack’. Divine existence can only be fully ‘real’ if it is consciously perceived, and even praised, by consciousnesses that are themselves ‘real’. A divine existence infinitely ‘alone’, with no consciousness ‘other’ than itself, would be comparable to a kind of somnolence, a dream of essence, the dream of an essence ‘unconscious’ of itself. The Creator needs other consciousnesses if he is not to be absolutely alone in enjoying his own glory, if he is not to be absolutely alone in confronting his infinite unconsciousness, without foundation or limit.

Man possesses his own consciousness, woven of fragility, transience, evanescence and nothingness. His consciousness can reflect on itself and on this nothingness. Each consciousness is unique and unrepeatable. Once it has appeared on earth, even the most omnipotent God can’t undo the fact that this consciousness has been, that its coming has taken place. God, in his omnipotence, cannot erase the fact that this singularity, this unique being has in fact existed, even if he can eradicate its memory forever. Nor can God, despite his omnipotence, be both « conscious » as « God the Creator », and conscious as is “conscious” a « created creature ». He must adopt one of these points of view. He has to choose between His consciousness (as being ‘divine’) and the specific consciousness of the creature. Nor can He simultaneously have full and total awareness of these two kinds of consciousness, since they are mutually exclusive, by definition. The potter’s point of view cannot be the pot’s point of view, and vice versa.

But can’t God decide to « incarnate » Himself in a human consciousness, and present Himself to the world as a word, a vision or a dream, as the Scriptures testify? But if He « incarnates » in a man (or a woman), doesn’t He lose to some extent the fullness of His divine consciousness, doesn’t He dissolve His Self somewhat, doesn’t He become partly unconscious of His own divinity, by assuming to incarnate in a human consciousness? In essence, all consciousness is one; it unifies and is unified. All consciousness is a factor of oneness, in itself, for itself. God Himself cannot be simultaneously ‘conscious’ as a conscious man is, and ‘conscious’ as a conscious God is, a One God. A One God cannot at the same time be a double or split God.

We can take another step along this path of reflection. In the depths of the divine unconscious lies this sensational truth: knowledge of the unique, singular consciousness of every human being is not of the same essence as knowledge of the unique, singular consciousness of God. These two kinds of knowledge are mutually exclusive, and if the former escapes entirely from the latter, the latter also escapes, in part, from the former. Every consciousness remains a mystery to all other consciousnesses. The two kinds of consciousness, created consciousness and divine consciousness, cannot merge into a pure identity, but they can enter into dialogue.

Could it be, however, that the unique, singular, created consciousness of each creature is in some way part of God’s unconscious? This question is not unrelated to the hypothesis of a possible divine Incarnation. Before the beginning, the very idea of a Man-God (or of God incarnating Himself in His creation) did not exist. There was only one alternative: God, or ‘nothing’. After Creation took place, the situation changed. There is now God—and ‘something’ else. We must recognize the hiatus, and even the fundamental chiasmus of consciousness caught between these two essences, these two realities, the divine and the created. If Man is conscious in his own (unique, singular) way, how can the God (unique and singular) recognize this uniqueness, this singularity of human consciousness, if He can recognize no ‘other’ consciousness, no ‘other’ uniqueness, no ‘other’ singularity, than His own? If God, being ‘one’, cannot recognize an ‘other’ than Himself, He cannot recognize in Himself the absolute ‘other’. He is therefore not absolutely conscious of Himself, of His own consciousness, of His own uniqueness and singularity, if He is not also conscious of the presence of this ‘other’ within Himself. And, being unconscious of what is absolutely ‘other’ in Him, how could the God glorify in Man’s consciousness, from the point of view of His absolute uniqueness, which, as such, is unconscious of all otherness?

A similar question was formulated by Jung: « Could Yahweh have suspected that Man possesses a light that is infinitely small, but more concentrated than that which he, Yahweh, possesses? Perhaps jealousy of this kind could explain his behavior263. » Is Yahweh really a jealous God, in the literal sense? Is God ‘jealous’ of Man? The expression « jealous God »—El qanna’—is used several times in the Hebrew Bible. It’s the name by which YHVH calls Himself (twice) when He appears to Moses on Mount Sinai: « For YHVH, His name is ‘Jealous’, He is a jealous God264! » This name has consequences for man, in a way that can be considered humanly amoral: « For I, the Lord, your God, am a jealous God, who pursues the crime of fathers on children to the third and fourth generation, for those who offend me265. » And, no, this jealous God doesn’t forgive, he wants revenge. « The Lord is a jealous and avenging God; yes, the Lord takes vengeance, he is capable of wrath: the Lord takes vengeance on his adversaries and holds a grudge266. »

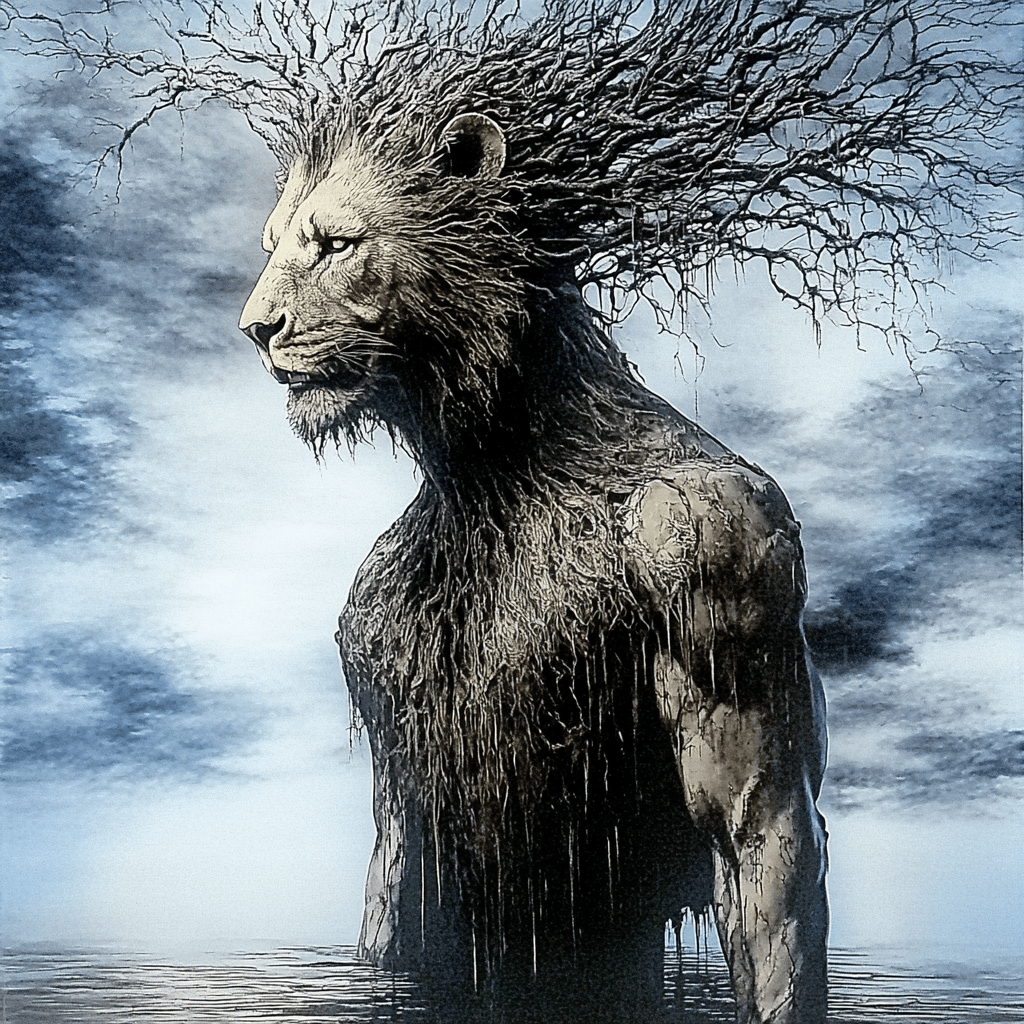

Jung also claims that Job was the first to understand the contradiction of God being omniscient, omnipotent and « jealous » all at the same time. « Job was elevated to a higher degree of knowledge of God, a knowledge that God Himself did not possess […] Job discovered God’s intimate antinomy, and in the light of this discovery, his knowledge attained a numinous and divine character. The very possibility of this development rests, we must assume, on man’s ‘likeness to God’267. » If God does not possess the knowledge that Job does, we can say that He is partly unconscious. Now, the unconscious, whether human or divine, has an ‘animal’ nature, a nature that wants to live and not die. Indeed, the divine vision reported by Ezekiel was composed of three-quarters animality (lion, bull, eagle) and only one-quarter humanity: « As for the shape of their faces, all four had the face of a man and on the right the face of a lion, all four had the face of a bull on the left and all four had the face of an eagle268. » From such « animality », so present and so prominent in Ezekiel’s vision of God, what can a man reasonably expect? Can (humanly) moral behavior be (reasonably) expected of a lion, an eagle or a bull? Jung’s conclusion may seem provocative, but it has the merit of being coherent and faithful to the texts: « YHVH is a phenomenon, not a human being269. »

Job confronted the eminently non-human, phenomenal nature of God in his own flesh, and was the first to be astonished by the violence of what he discovered, and what was revealed. Since then, man’s unconscious has been deeply nourished by this ancient discovery, right up to the present day. For millennia, man has unconsciously known that his own reason is fundamentally blind, powerless, in the face of a God who is a pure phenomenon, an animal phenomenon (in its original, etymological sense), and certainly a non-human phenomenon. Man must now live with this raw, irrational, unassimilable knowledge. Job was perhaps the first to elevate to the status of conscious knowledge a knowledge long lodged in the depths of the human unconscious, the knowledge of the essentially antinomic, dual nature of the Creator. He is at once loving and jealous, violent and gentle, creator and destroyer, aware of all his power, and yet, not ignorant, but at least unaware of the unique knowledge that every creature also carries within. What is this knowledge? In Man, this knowledge is that his consciousness, which is his unique and singular wealth, transcends his animality, and thus carries him, at least potentially, into the vertical vertigo of non-animality. This establishes the likelihood of ancient links between monotheistic spirituality and the various shamanic forms of spirituality, so imbued with the necessity of relations between humans and non-humans.

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.